29 September 2020

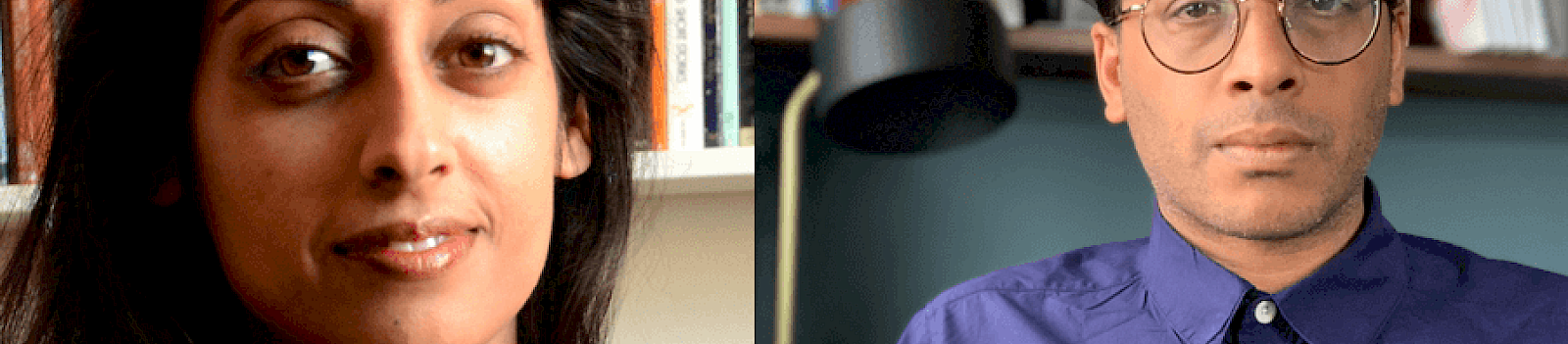

Beyond benign notions of ‘diversity’: Sandeep Parmar and Anamik Saha in Conversation

Earlier this summer, two reports shook up the publishing landscape in the UK.

The first, the Ledbury Poetry Critics 2020 annual report, The State of Poetry and Poetry Criticism in the UK, carried out by Dr Dave Coates and released by the Ledbury Poetry Critics Programme (of which Sandeep Parmar is co-founder). And the second, Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing, led by Dr Anamik Saha and Dr Sandra van Lente – in partnership with Goldsmiths University, Spread the Word and The Bookseller – which is the first academic study in the UK which looks at how cultural production itself might disadvantage writers of colour.

In an exclusive for Wasafiri, Sandeep Parmar and Anamik Saha discuss the two reports, the state of publishing and reviewing in the UK, and what the future holds.

Wasafiri: Could you both summarise your reports for those who haven’t read them? What was your most surprising discovery?

Sandeep Parmar: The State of Poetry and Poetry Criticism in the UK is largely a quantitative analysis of non-white poets, critics, prize-winners and editors undertaken by Dr Dave Coates, who like me is based at the University of Liverpool’s Centre for New and International Writing. Dave and I co-authored the qualitative analysis which, like the data, makes a case for greater diversity in UK poetry and demonstrates the ongoing progress made by the Ledbury Poetry Critics programme. We found that between 2009 and 2016, British and Irish poetry magazines and newspapers published review articles by non-white critics 190 times or 4% of the total for those years. In the three years since the launch of the Ledbury Critics Programme in 2017, critics of colour have been published on the same platforms 201 times or 9.6% of the total for these years. In fact, coverage of poets of colour, and coverage by non-white critics, have both (more than) doubled in the three years since the launch of the Ledbury programme in 2017. It’s quite a trajectory: just 8 articles by non-white critics were published in 2009; there were 75 in 2019. Some magazines/newspapers fared very badly in the count: The London Review of Books has published 105 articles by 39 different poetry critics. All 39 were white. Those 105 articles reviewed 127 different books and all 127 were by white poets.

This year we looked more closely at the stats in order to avoid the aggregate term ‘BAME’: we found that Asian critics are almost three times more likely to appear than black critics (2.6% of total reviews).

Anamik Saha: As the title suggests, with Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing we wanted to shift the publishing industry’s approach to diversity. Fixing ‘diversity’ usually involves a focus on numbers and initiatives that aim to get more minorities in the industry. While improving the diversity of the creative workforce is obviously important, it is a mistake to assume that this will automatically lead to more diverse representations of minorities in media output—which is surely the point of making creative and cultural industries more representative. In my previous research I have found that black and Asian cultural producers in particular find themselves steered into reproducing racial and ethnic stereotypes, despite their attempts to do otherwise. With this research we wanted to explore in much detail how this process actually unfolds, with a specific focus on publishing. For this purpose we conducted over a 100 interviews with people who across the three main stages of the publishing process: 1) agenting/acquisition, 2) book promotion, and 3) sales. In a nutshell we found that the publishing industry – or at least the big publishers – are generally only interested in a single reader: white, middle-class (and female). It was surprising to hear that this still remained the case! As such authors of colour are essentially acquired, packaged, promoted and sold in a way that is made to appeal to this very narrow demographic. This explains why representations of racial and ethnic minorities in books so often reproduce the same racial/Orientalist tropes that confirm to white, middle-class expectations of those minority groups.

A quote from the Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing report:

'One of the many topics that we did not have the space to address in this report, was how publishers’ desire for more writers from disadvantaged backgrounds can stem out of fear or embarrassment of not being seen as inclusive. Social media has enabled audiences to publicly talk back to publishers in a way that was never the case before, to the extent they can make or break books. Fear and shame in this instance are generating new opportunities for minority and working class writers. But it seems far from ideal when the push for diversity is more about preventing reputational damage than solving structural inequalities.’

Can you both discuss this performative versus structural change? SP: I agree completely with the observation here, Anamik, about publishing generally. But perhaps in publishing the forces of shame and fear work differently than they do in poetry reviewing, which is less visible and less market driven (and so, conversely, much more dependent on the tastes of commissioning editors and critics). Which is to say that reviewing relies on the book market but there’s no market for reviewers—in this way although there are favoured (and indeed powerful) book critics there’s not much of a sense that they’re so highly distinctive from each other as to be more authoritative than the platforms they write for (unlike film critics, perhaps, but I digress). So reputational damage is not really a factor (hence the whiteness of the LRB, TLS, PN Review and other respected outlets). The readership for poetry reviews in magazines will also vastly differ to those for (the few remaining poetry) newspaper reviews. The poetry critic, and critics generally, see themselves as specially informed readers and so this naturally sets them apart from what they might perceive as public opinion, giving rise to protectionist reasoning that rarely seems credible (about craft, aesthetics, authenticity, identity politics). Structural change in commissioning non-white poetry critics will most meaningfully come about with non-white editors; for now, because in poetry reviewing widespread censure from the community doesn't quite work, I doubt it is wholly performative that white editorial allies have implemented change. The least diverse publications tend to be newspapers or the LRB and the TLS, which also have the largest readerships and so far we've seen very little movement at those papers. AS: Poetry is part of the publishing industry but as you say Sandeep, works according to its own logics and practices. While publishers of fiction – even in commercial genres – find it difficult to describe their books as ‘commodities’ I think this is even harder for poetry editors and critics. From the outside, it seems to me that poetry is such a bubble that it manages to avoid the same scrutiny as the rest of the publishing world, which is why your report on The State of Poetry and Poetry Criticism is so urgent. In our report that looked specifically at the fraught issue of race in the production of genre fiction, we found that the thing that publishers fear the most is a social media backlash around perceived racism that can effectively destroy the sales of a book (I refuse to use the word ‘cancel’!). Note the increasing prevalence of the ‘sensitivity reader’, who are readers who have an insider perspective of a particular marginalised experience (whether in terms of race, disability, religion, transexuality and so on) hired by editors to ensure that characters from that marginalised background are represented correctly. In addition, such a negative response is an unwelcome challenge to publishers’ overwhelmingly liberal sensibilities. While publishers’ increasing – or rather, long overdue – recognition of their industry's institutional whiteness and middle-classness has inevitably produced some opportunities for writers of colour (to the extent that one editor we interviewed said that it is an ‘advantage’ right now to be a black of brown writer) as the above quote suggests, we have a deep ambivalence about some of the ways publishers are tackling this. Quite simply ‘diversity' appears to be about more about maintaining brand value rather than redressing actual structural inequalities. It is no coincidence that the new diversity officer roles that have been created in the bigger publishing houses are situated within communication/HR departments rather than in editorial. There have been several reports on diversity—and its lack in publishing. The most common response it seems, institutionally, to issues of discrimination, is to commission enquiries and ‘listen’. What do you perceive as the necessary steps to move reports from ideas and accounts to action? SP: Reports like Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing are incredibly valuable and the Ledbury 'State of Poetry and Poetry Criticism' reports are the only real measure of change in poetry reviewing ever commissioned. Numbers are just very effective at making people take note. However, in order to translate these measurements into lasting change much more collaborative work is needed, which is what we hope will be the next phase of the Ledbury Poetry Critics programme. As noted above, since the LPC founding in 2017 poetry reviewing by non-white critics has more than doubled from 4% to 10%. Now, without losing the momentum with commissioning reviewers of colour, we're keen to consider the language of reviewing and race, how poets of colour are framed and how their work is discussed: a qualitative approach supported by quantitative data. For example, it is unacceptable that in 2020 a poetry review in the Guardian could lump a group of poets together under the term 'Anglo-Asian'. There's just no excuse for that poverty of critical language. That must change. AS: ‘Anglo-Asian’! I think this captures the very problem with the literary elite! We are proud of our report but see enacting actual real change as the biggest challenge. With Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing, our primary task was shining light on the obstacles and challenges facing authors of colour and the representation of race in publishing more generally. But there is, rightly perhaps, an expectation from the industry that such a report must provide solutions to the problems. While we endeavoured to offer practical recommendations, is a bullet point list of ‘best practices’ really going to tackle the deep racial inequalities that characterise perhaps the most privileged of cultural sectors? Real change we believe is going to entail structural change, including forms of policy that put the means of cultural production into the hands of people of colour. For instance we would like to see more state support for ‘BAME’-led independent publishing platforms. I anticipate that this idea will receive some pushback from the big publishing houses. But at the very least, our hope with the report is that it opens up conversations within publishing houses and encourages them to rethink their assumptions regarding how authors of colour have been traditionally acquired, promoted and sold. This emphasis on merely 'rethinking’ might feel like bit of a let-off for publishers, agents and booksellers, but the response we have had has suggested that the industry recognises that it needs to challenge their assumptions around race. The way that the launch of the report coincided with the recent #BlackLivesMatter protests was purely coincidental but gave the report a greater urgency. #BlackLivesMatter has produced a profound reckoning with race in Western societies that, until recently had flattered themselves into thinking that they are ‘postrace’. This affect has extended to the publishing industry where publishers have been forced to look inwards and consider their own racism. Let us see what real change such critical reflection will bring. And, on a related note, is there such a thing as ‘report fatigue’? These statistics are, in some ways, shocking, but not surprising. On social media, such reports have shelf lives—you see sharing and re-sharing and raging on Twitter for a week and then something else takes its place. Can you talk to the longevity and long-lasting impacts (changes, future challenges) of this research and report making? SP: As I've said, there are ways to think about the long-term aims for our respective industries/disciplines. It is not entirely up to the authors of any report to delineate what those aims are—in fact lasting change requires an open discussion that is collaborative and collective. LPC certainly does not want to centre itself in what must be a sector-wide movement towards better and more diverse poetry criticism. And, yes, reports do have limited shelf lives and of course the numbers aren't all that surprising to anyone paying close attention. But poetry – at certain editorial levels – still harbours opinions about whiteness and cultural value that no amount of reporting will change. What needs to happen next is a changing of the guard, a decolonising of criticism and its institutions. While there are still (largely white male) editors and poets who think 'identity politics' is a plot against all that is culturally valuable real progress will be slow and piecemeal. AS: Your comments about cultural value hit the nail on the head, Sandeep. In our research we found that notions of ‘quality’ – that are perceived as universal rather than a very white, bourgeois particular – are what hold back authors of colour. It is the discourse within which writers from marginalised background are either rejected or granted entry. And it is so entrenched in the entire culture of publishing that it is hard to believe how a report is going to even budge let alone radically transform notions of value as enacted in publishing. But there are some differences between poetry and trade fiction, which gives me some grounds for hope for writers working in the latter. While we were expecting fatigue around the discussion of ‘diversity’ we actually found the opposite. In fact there was great enthusiasm to participate in the research and we exceeded the number of interviews we wanted to conduct (we conducted well over 100 interviews, where 60% of our respondents were white). Moreover we did not encounter any fatigue or defensiveness around the issue of lack of diversity in publishing. While the stark whiteness of the industry is a hard thing to deny, we nonetheless did believe our white respondents’ assertions that they need to do better. Thankfully as well, the response to the report itself and to the events we organised as part of the launch certainly exceeded my expectations and again, showed no signs of weariness on the part of publishers. Admittedly everyone talks a good game on social media—which goes back to my original point about diversity as brand value. Nonetheless I was pleased to see some evidence of meaningful, critical reflection. Yet as much as I am the co-author of one, I have doubts about the power of reports—not least in their ability to singlehandedly fix entrenched racism. It is for that reason I always return to Stuart Hall’s take on the Gramscian notion of a war of position: a politics based around culture is not about achieving total victory but trying to pull hegemony and what constitutes ‘commonsense’ in more progressive directions. I find that this helps relieve the burden of what a report can be expected to achieve by itself! What were/are some of the challenges you’ve faced in working on your respective reports—for example, in terms of access to facts and figures, critiques and counter-critiques from within the industry? SP: There have been examples of the aforementioned white male editor or critic feeling that their authority over an unchanging landscape is threatened by racial diversity. They seem to have no shortage of outlets for their anxieties. But, on the whole, the Critics programme, and calls for greater diversity in reviewing have been met with huge support by editors, critics, readers. Review space in broadsheets is dependent on interest from readers so the market is quite precarious for poetry. Poetry magazines that invest in high quality critical writing must also be supported—or else we'll lose them. That's the biggest challenge: the dwindling space for poetry reviewing itself. Otherwise, LPCs stats, like other such organisations, rely on counting what is in the public domain—and self-reporting data on race and gender, etc, would be more effective if it was consistent (which is also very hard to guarantee – see VIDA's struggles with this). We could opt collectively for methods of sector-wide compulsory reporting with agreed-upon measures, equally applied, and complete transparency. That would provide better quality data of course. But ultimately what matters most is that anyone who is genuinely invested in racial equality looks to the left, the right, across the table, and sees who is represented there and who is not. And then reflecting on it, acts. AS: As I said, we did not really encounter too much guardedness. But maybe because what we proposed was not too hard-hitting—our primary method was interviews where we wanted to get a broad sense of how agents, publishers and booksellers approach their roles and working with authors of colour in particular. We had to reassure our respondents that this was not an interrogation! Saying that, our initial aim in fact was to do an ethnographic study of a publishing house, including gaining access to acquisition and sales meetings to see how authors of colour are treated. Perhaps unsurprisingly the big publishing house we had approached with this idea politely declined. If our research was based more around obtaining statistics on the racial/ethnic make-up of publishing houses, on comparative pay, or the number of authors of colour published I think this too would have bigger challenge. As corporate entities publishing houses are cagey about giving access to academic researchers for all the obvious reasons. Indeed, this is what makes this kind of research into cultural production so difficult to conduct. Overall we were pleased with the level of access we did gain, including some very senior people. And as I said, we encountered little hostility and defensiveness. But again, everyone talks a good game, especially when the reputation of the publishing house is at stake. While the response on Twitter has been overwhelmingly positive the real challenge is to get the report discussed at board-level. I am really hopeful that both of our reports can help shift agendas and the way that issues of ‘diversity’ are conceptualised and tackled. Building a new consensus around how issues of race and racism are talked about in publishing, including poetry, is an initial but vital step in a war of position. What’s next for the industry? SP: Hard to say. But what I’d like to see is a push for more poetry editors and commissioning editors of colour—this seems to be the only way to guarantee that we aren’t allowed to rebound into mostly white male editors hiring their mostly white male reviewer friends to review mostly white male poets. The most exciting editors working in poetry today come from a variety of backgrounds—I’d like to see more of this and a renaissance for poetry reviewing where newspapers don’t cut poetry review space but grow them to match an increasing enthusiastic engagement among readers and poets. AS: My hope with the report is that it will encourage agents, publishers and booksellers to rethink commonsense understandings of authors of colour and their commerciality/value. This needs to extend to their understandings of ‘minority’ audiences. Fundamentally, the publishing industry sees authors of colour as a risky investment. As such authors of colour encounter tighter forms of creative control than their white counterparts. As soon as publishers realise that the assumptions that they hold are just that, assumptions, rather than truths, the better. Maybe this report will nudge them in this direction. Otherwise it is going to be up to black and brown writers, publishers and readers to challenge the core industry all the way. Similarly to Sandeep, I am particularly excited by the new generation of publishers – both black and white – who work according to a social justice agenda, as much as an entrepreneurial one. And to repeat myself, what we need are new forms of policy that can financially support these publishers, specifically the ones who are working independently. Moreover I argue that this needs to be done in the name of reparative justice rather than benign notions of ‘diversity’ but that is an argument for another time! Sandeep Parmar is Professor of English Literature at the University of Liverpool. She holds a PhD from University College London and an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. Her research interests are primarily modernist women’s writing and contemporary poetry and race. Her books include: Reading Mina Loy’s Autobiographies: Myth of the Modern Woman, scholarly editions for Carcanet Press of the Collected Poems of Hope Mirrleesand The Collected Poems of Nancy Cunard as well as two books of her own poetry: The Marble Orchard and Eidolon, winner of the Ledbury Forte Prize for Best Second Collection. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the Guardian, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The New Statesman, the Financial Times and the Times Literary Supplement. She is a BBC New Generation Thinker and Co-Director of Liverpool’s Centre for New and International Writing. In 2017, she founded the Ledbury Emerging Poetry Critics Scheme for BAME reviewers and the Citizens of Everywhere project which focuses on broadening ideas of citizenship and belonging. Anamik Saha is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media, Communications and Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. His research interests are in race and the media, with a particular focus on cultural production and the cultural industries, including issues of ‘diversity’. He is the author of Race and the Cultural Industries, published by Polity in 2018. In 2019 he received an Arts and Humanities Research Council Leadership Fellow grant for a project entitled ‘Rethinking Diversity in Publishing’, which led to a report published by Goldsmiths Press in June 2020. Anamik is an editor of European Journal of Cultural Studies. His new book entitled Race, Culture, and Media (Sage) is out in Spring 2021. This piece is published as part of the online coverage for our latest issue, Wasafiri 103 – featuring a special section on Writing Whiteness – which you can purchase here.