22 September 2020

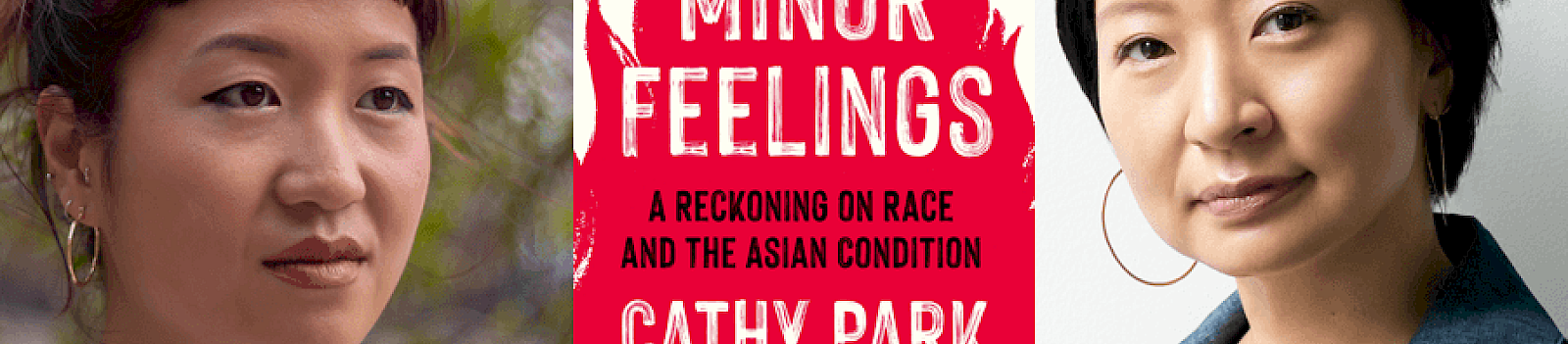

Cathy Park Hong and Minor Feelings

Cathy Park Hong is a Korean-American poet and essayist who is the author of three volumes of experimental poetry. Her most recent work is the non-fiction book, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, which deftly and unforgettably explores the shame, suspicion and melancholy that permeates the Asian-American experience. With humorous and incisive precision, Hong articulates the complex permutations of self-loathing and self-consciousness that arise when minority experiences are constantly dismissed by a white world that refuses to acknowledge the specific contours of reality.

Sharlene Teo’s debut novel Ponti won the inaugural Deborah Rogers Writer’s Award, was shortlisted for the Hearst Big Book Award and Edward Stanford Fiction Award, longlisted for the Jhalak Prize and selected by Ali Smith as one of the best debut works of fiction of 2018.