Feature image by Jeremy Bishop from Pexels via Canva.com

From Our Waters by Nuraliah Norasid

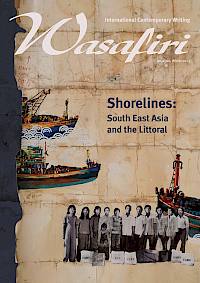

Read an exclusive extract from this atmospheric, immersive, and haunting short story, which was first published in Wasafiri 116: Shorelines: South East Asia and the Littoral, our winter special issue co-guest edited by Nazry Bahrawi, Joanne Leow, and Y-Dang Troeung. This issue focuses on a range of creative, critical, and artistic work from Singapore, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, and Myanmar, and their diasporas.

I. PRIMORDIAL

She cannot move. As if her muscles have been paralysed by the cave’s opening stare. She does not comprehend the dark, skulking shadow of a wolf-like creature nearby, as it oscillates, padding on soft paws, between the dim light and the darkness from the deep recesses of the cave.

The shadow stops, one paw raised in mid-step. Then it draws back and sits on its haunches. The gibbous moons it has for eyes disappear and reappear in sporadic winks. For a moment, one might see a dark hint of red as it yawns.

It is in no hurry.

When the water rises soon after and takes the straggler away, the dark figure does not chase after it, only pad over to the bodies of the others who are either too weak or too far away from the river to make it and sniffs at them with wet flares of its nostrils.

The high tide carries her out into the empty sunlight. A wave throws her towards the rock wall outside of the cave’s opening before pulling her into the sea. Within it, she dives deep and propels her limbs for a distance so that she will not be dragged back to the rock wall before letting the current take her. Her hair writhes and pulses, providing her propulsion and, as multi-umbilici, draws in plankton from the water to keep her alive.

She drifts and bobs. Eventually, her skin loses its translucence. She moves her fingers, making simple grasping motions with her hands. She kicks her legs with some purpose. She switches from plankton to small fish and crustaceans, missing the snapping mouths of seals and eels by mere centimetres.

In daytime, there is something about the vastness above that draws her to it. Her film-veiled eyes catch the sun, its brightness rubbed into the shimmer. She, partly drifting, partly swimming, rises to try and meet it.

II. WHERE WATER AND JUNGLE MEET

A break from the water comes in the form of another large sea creature. It swims with ease despite its lumbering physique. Its mouth in a perpetual yawn, its mane flowing in thick kelp strands back from its head, framing a strange, leonine face. There is a scarred patch where no mane grows, from the time it surfaced for air during a thunderstorm. The rest of the creature’s body is covered in scales ending at points in rounded fins and a long truncate tail.

She grasps at a streaming mane as it swims past her, catches it and burrows herself to the shiny, crinkled scalp.

Where she is safe, until the odd sea creature comes to a small chunk of emerald land and, driven by some inexplicable desire to go inland, makes the mistake of swimming through the mouth of a tiny river, where it gets stuck in a narrow bottleneck. The creature finds itself incapable of tuning around and in its panicked struggling, blowing out more air than it is breathing in, ends up on the riverbank, flopping about like a common fish out of water. Under the merciless tropical sun, it curls up, tailing point towards its mouth. Its body hardens and everything about it, from mane to scales, is bleached a limestone white.

It is said that she is flung out into the line of jungle by the river, where she falls among the undergrowth, landing on a carpet of dried fallen leaves, throwing up a cloud of them. A startled monitor lizard darts out of sight. A cobweb breaks in the process.

She stares at the treetops, listens to them crackling as the leaves move against each other in the nearly-imperceptible breeze, the sky showing through in pale, broken shards, before balling her hands into tight fists on either side of her. She screams. It is not long before her skin begins to attract ants and this makes her cry louder, kicking up a fuss in the air above her.

III. OLD HANA

The undergrowth rustles and a tiny old woman emerges from behind the buttress roots of a tree ahead. She is bent from the load of a cloth bundle slung across her back. In one hand, she holds a broken off branch which she uses as a walking stick, and she wears her grey hair pulled into a snail knot, away from a face more wrinkled than the surface of the sea. Veins bulge on her bare feet. She wears a cerulean sarung batik, decorated in leaves and sunbursts of orange flowers, hitched up high under a pale patterned blouse.

She heard the young one crying while foraging, and right then she watches the infant, without moving or reaching out for it. Watches as it fusses and kicks, its screaming ringing through the undergrowth, the urgency of the sound rendering all silent. It is not the first time that she has seen an infant in these parts of the forest, so close to the sea that one can hear the waves if they listen hard enough. However, she would usually find such infants on the ample pedestal of the old gravestone a little further inland. Many residents of the island believed that the grave belongs to a holy woman, whose spirit will grant the child a miracle and therefore allay them of their guilts.

But it is she, that all know as Old Hana, who retrieves them later, cold and unmoving, or very nearly so.

‘You,’ she says often to the headstone, ‘look at what you have inspired.’

Of course her sister, who died in childbirth so many years ago, cannot respond.

After the initial failed attempts at reviving them, she has learnt to wait, to see the infants draw their last breaths. Sometimes, it takes hours.

So, now she waits, but the infant’s crying does not seem to be subsiding, even as the day threatens night.

Finally, weary from beating at her legs to keep the ants off, she approaches the infant and sees that it is no ordinary one. Its skin is too dark, not like soil or a moonless night around the edges of a lamplight, but the bruising purple-blue, uniform and prominent around the bright red of its open mouth. The infant’s hair is unnaturally long and fans out around its face, bearing the texture and appearance of the seagrass that one often finds exposed along the shore during a low tide.

Old Hana gazes in the direction of that very shore, wondering at what manner of parents produced and abandoned this creature. Is it the progeny of a coupling between a spirit and one of the fisherfolk? ...

Continue reading the full piece online, free to download for the month of January, or in Wasafiri 116.

Wasafiri 116: Shorelines: South East Asia and the Littoral, our special winter issue guest edited by Nazry Bahrawi, Joanne Leow, and the late Y-Dang Troeung, features a range of creative, critical, and artistic work from Singapore, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, and Myanmar and their diasporas, exploring the littoral encounter of existing on the shoreline.