19 August 2019

'Get Up, Stand Up Now': Zak Ové speaks to Susheila Nasta

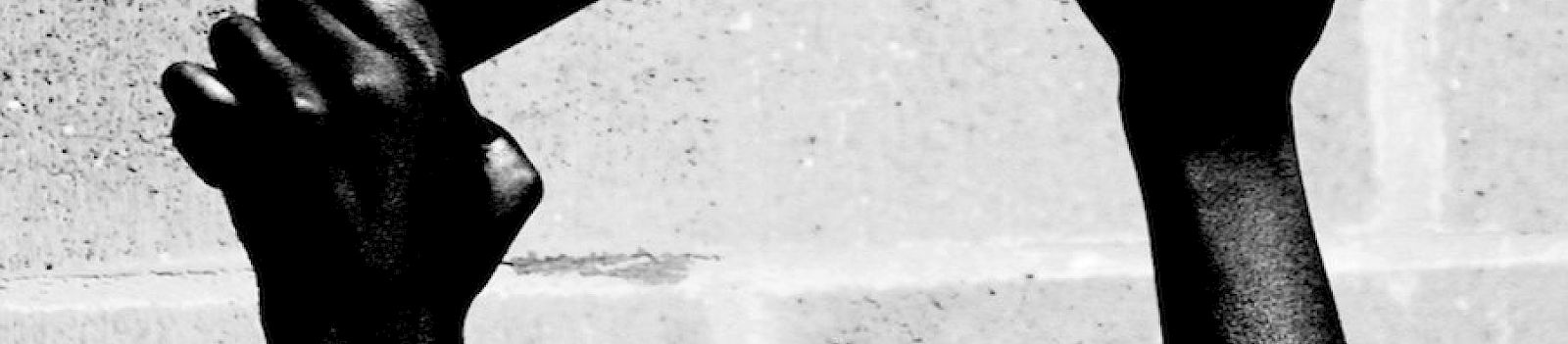

Libita Clayton, ‘BS2-RESIST & REVOLT BLACK HISTORY, LIVE TRANSMISSION’. Image courtesy of artist.

Zak Ové, London-based multi-disciplinary artist and cover artist of Wasafiri issue 100, talks to Susheila Nasta about the background to curating ‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’, a major exhibition at Somerset House celebrating the last fifty years of black creativity in Britain and beyond. Susheila Nasta: Can you say something about why 2019 is the right moment and what has inspired you to curate this exhibition? Zak Ové: It’s way overdue, a show like this, but now especially in light of the recent Windrush scandal, which saw West Indians who had long resided in Britain wrongly classified as illegal immigrants and deported 'back home'. Housing the exhibition at Somerset House, which served at the height of empire as the Royal Navy’s administrative centre, lends it an extra charge. I think it’s always been necessary to have an exhibition like this. Then, now and in the future, we should have more shows about Black creativity in the UK, exploring the dialogue between Black artists and how they are communicating the Black experience. [caption id="attachment_6160" align="alignright" width="300"] Victor Ekpuk’s ‘Shrine to Wisdom’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

What is the time span and how did you select the artists and writers to feature?

I started by looking at my father Horace’s archive. He created his first film [Baldwin’s Nigger] 50 years ago – so that was the time span – 50 years. I was born into an artistic family and brought up in an extended artistic family. Many practitioners of the Windrush generation became parental to me. Quite literally, I began with all of them.

I started to explore who their work was talking to, the next generation of artistic cousins who were inspired by them and took forward similar themes. It included musicians, filmmakers, writers—and not just from Britain. And then, further down the line, today’s brilliant young talent, who have been influenced by the children of my father’s generation. Each generation stands on the shoulders of their elders. Regardless of age and boundaries, I realised there was a shared experience throughout these different mediums and timelines, and throughout the diaspora. And it just excited me. This is why the show is thematic, rather than chronological.

I identified and invited artists who have similarly made a significant contribution to shaping this country’s creatives and the cultural landscape in general. Pioneering work that challenges the systems of power and representation and continues to change the consciousness of society today through perpetual agitation.

[caption id="attachment_6152" align="alignleft" width="221"]

Victor Ekpuk’s ‘Shrine to Wisdom’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

What is the time span and how did you select the artists and writers to feature?

I started by looking at my father Horace’s archive. He created his first film [Baldwin’s Nigger] 50 years ago – so that was the time span – 50 years. I was born into an artistic family and brought up in an extended artistic family. Many practitioners of the Windrush generation became parental to me. Quite literally, I began with all of them.

I started to explore who their work was talking to, the next generation of artistic cousins who were inspired by them and took forward similar themes. It included musicians, filmmakers, writers—and not just from Britain. And then, further down the line, today’s brilliant young talent, who have been influenced by the children of my father’s generation. Each generation stands on the shoulders of their elders. Regardless of age and boundaries, I realised there was a shared experience throughout these different mediums and timelines, and throughout the diaspora. And it just excited me. This is why the show is thematic, rather than chronological.

I identified and invited artists who have similarly made a significant contribution to shaping this country’s creatives and the cultural landscape in general. Pioneering work that challenges the systems of power and representation and continues to change the consciousness of society today through perpetual agitation.

[caption id="attachment_6152" align="alignleft" width="221"] Ronan McKenzie, ‘I’m Home, 3 Moments’. Copyright of the artist.[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_6155" align="alignleft" width="230"]

Ronan McKenzie, ‘I’m Home, 3 Moments’. Copyright of the artist.[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_6155" align="alignleft" width="230"] Yinka Shonibare OBE, ‘Self-Portrait after Warhol’. Photo credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

Part of this exhibition, indeed a large part, features the work of your father Horace who is well known as a filmmaker and photographer and cultural activist. Can you talk about what elements of his career inspired you and how you feel the influences of this pioneer generation of Caribbean, black British and South Asian artists continues to reverberate today?

My practice grew from watching my father persist as an artist and an activist, watching him create films and photography and use his vision and voice to vocalise and illustrate his dream to change the world. He documented and dramatised the Black experience and those who stood up proudly against all odds, against all forms of inequality and racism. I’m a passionate believer in radical integration and it’s through culture that we become more harmonious and multicultural as a collective people.

My father, and indeed many of our ‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ contributors, never waited for a commission to do this, because it probably would never have come to them. They have broken ground because they got on with creating something that so heartfeltly spoke about the issues they face, rather than hanging on for someone to recognise it along the way and ask them to produce it, and their work has truly connected as consequence. Also it meant they didn’t have to fit within the confines of the commission; they could be creative polymaths – film, photography, sculpture, whatever they wanted to turn their hearts and hands to, they did.

I think it’s this can-do spirit that has inspired me most, and others today too, and their sense of pride—not worrying if it’s allowed or not. We can say: ‘This is my soul, my beliefs and my ancestry, and I want to revere it’, no matter what anyone else may tell you.

[caption id="attachment_6156" align="alignright" width="300"]

Yinka Shonibare OBE, ‘Self-Portrait after Warhol’. Photo credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

Part of this exhibition, indeed a large part, features the work of your father Horace who is well known as a filmmaker and photographer and cultural activist. Can you talk about what elements of his career inspired you and how you feel the influences of this pioneer generation of Caribbean, black British and South Asian artists continues to reverberate today?

My practice grew from watching my father persist as an artist and an activist, watching him create films and photography and use his vision and voice to vocalise and illustrate his dream to change the world. He documented and dramatised the Black experience and those who stood up proudly against all odds, against all forms of inequality and racism. I’m a passionate believer in radical integration and it’s through culture that we become more harmonious and multicultural as a collective people.

My father, and indeed many of our ‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ contributors, never waited for a commission to do this, because it probably would never have come to them. They have broken ground because they got on with creating something that so heartfeltly spoke about the issues they face, rather than hanging on for someone to recognise it along the way and ask them to produce it, and their work has truly connected as consequence. Also it meant they didn’t have to fit within the confines of the commission; they could be creative polymaths – film, photography, sculpture, whatever they wanted to turn their hearts and hands to, they did.

I think it’s this can-do spirit that has inspired me most, and others today too, and their sense of pride—not worrying if it’s allowed or not. We can say: ‘This is my soul, my beliefs and my ancestry, and I want to revere it’, no matter what anyone else may tell you.

[caption id="attachment_6156" align="alignright" width="300"] Zak Ové, 'Umbilical-Progenitor'. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/Somerset House[/caption]

There must have been a huge amount of material to sift through and a complex selection process. What were the key elements driving decisions about what to highlight and display?

Each artist has been invited to exhibit due to the significant role that they have played in terms of shaping our country’s cultural landscape and in translating their local and personal experiences into a universal language to which we can all relate.

I have selected artists from Africa, America, the Caribbean and Britain as these are the places and cultures that have influenced me and my father and that continue to inspire a diasporic cultural exchange.

[caption id="attachment_6167" align="alignleft" width="222"]

Zak Ové, 'Umbilical-Progenitor'. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/Somerset House[/caption]

There must have been a huge amount of material to sift through and a complex selection process. What were the key elements driving decisions about what to highlight and display?

Each artist has been invited to exhibit due to the significant role that they have played in terms of shaping our country’s cultural landscape and in translating their local and personal experiences into a universal language to which we can all relate.

I have selected artists from Africa, America, the Caribbean and Britain as these are the places and cultures that have influenced me and my father and that continue to inspire a diasporic cultural exchange.

[caption id="attachment_6167" align="alignleft" width="222"] Ishmahil Blagrove Jr’s ‘Free Speech Platform’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

Which artists have you featured prominently in the show?

‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ explores the development of black artists, filmmakers and musicians in the UK – from Windrush generation pioneers such as the photographers Vanley Burke, Armet Francis and Charlie Phillips to contemporary artists including Grace Wales Bonner, musicians such as Gaika, and the film director Jenn Nkiru. As well as focusing on the early practitioners of the 1950s and early 60s, the exhibition also shows how their work set the blueprint for a later generation including John Akomfrah, Steve McQueen and Sonia Boyce, who all have work in the exhibition.

Can you talk about why it was important to do this exhibition collaboratively and at Somerset House?

Britain’s cultural institutions are more open than ever before to Black British culture and the artists behind it; Black British artists are finally being properly represented in UK museums and galleries. Practically every major London institution has been built on the profits of the slave trade, as was the entire city of London in fact. I’m just so proud to be giving the recognition to my father and his creative peers, all members of the Windrush generation, that they thoroughly deserve and show how they have indelibly impacted the cultural fabric of our country.

One of the objectives has been to draw public attention to the successes of this older generation and their impact on Britain now. Can you talk about this in relation to your own work, your art and sculptures?

This is about the foundations of black British culture. My parents’ generation were informing their peers that we are part of British society like any other. They were enablers who delivered our culture into mainstream British culture, and now it’s permeated into all elements of British life.

At a time when populism is on the rise and the idea of a Britain divided along class, political and racial lines is growing, I hope the exhibition can show the UK is a country that has meshed together many cultural elements and is ultimately better off for it. Black British culture in this country is not separatist – we exist in British culture and we’ve brought our culture and there’s been an exchange. That’s been constant and it’s one of the things that makes Britain great.

[caption id="attachment_6157" align="alignright" width="300"]

Ishmahil Blagrove Jr’s ‘Free Speech Platform’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

Which artists have you featured prominently in the show?

‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ explores the development of black artists, filmmakers and musicians in the UK – from Windrush generation pioneers such as the photographers Vanley Burke, Armet Francis and Charlie Phillips to contemporary artists including Grace Wales Bonner, musicians such as Gaika, and the film director Jenn Nkiru. As well as focusing on the early practitioners of the 1950s and early 60s, the exhibition also shows how their work set the blueprint for a later generation including John Akomfrah, Steve McQueen and Sonia Boyce, who all have work in the exhibition.

Can you talk about why it was important to do this exhibition collaboratively and at Somerset House?

Britain’s cultural institutions are more open than ever before to Black British culture and the artists behind it; Black British artists are finally being properly represented in UK museums and galleries. Practically every major London institution has been built on the profits of the slave trade, as was the entire city of London in fact. I’m just so proud to be giving the recognition to my father and his creative peers, all members of the Windrush generation, that they thoroughly deserve and show how they have indelibly impacted the cultural fabric of our country.

One of the objectives has been to draw public attention to the successes of this older generation and their impact on Britain now. Can you talk about this in relation to your own work, your art and sculptures?

This is about the foundations of black British culture. My parents’ generation were informing their peers that we are part of British society like any other. They were enablers who delivered our culture into mainstream British culture, and now it’s permeated into all elements of British life.

At a time when populism is on the rise and the idea of a Britain divided along class, political and racial lines is growing, I hope the exhibition can show the UK is a country that has meshed together many cultural elements and is ultimately better off for it. Black British culture in this country is not separatist – we exist in British culture and we’ve brought our culture and there’s been an exchange. That’s been constant and it’s one of the things that makes Britain great.

[caption id="attachment_6157" align="alignright" width="300"] Yinka Shonibare’s ‘Revolution Kid (Calf)’ and Sanford Biggers’ ‘Woke’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

What would you like to come out of this exhibition and why is it so important now?

With over 100 artists from the post-war era to the present day, ‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ shows how each generation can stand on the shoulders of their predecessors and achieve even greater heights. The exhibition is loud, proud and unbowed, and we hope that it will inspire future creative professionals. I also hope that other gallery directors will take note – with shows like this one, and those that have come before like ‘Soul of a Nation’ at Tate, and 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, also at Somerset House, cultural institutions may sit up and realise the necessity of them. I hope, as a result, that more programmers will write it into their future scripts on a more regular basis.

[caption id="attachment_6162" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Yinka Shonibare’s ‘Revolution Kid (Calf)’ and Sanford Biggers’ ‘Woke’. Photo Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/ Somerset House[/caption]

What would you like to come out of this exhibition and why is it so important now?

With over 100 artists from the post-war era to the present day, ‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ shows how each generation can stand on the shoulders of their predecessors and achieve even greater heights. The exhibition is loud, proud and unbowed, and we hope that it will inspire future creative professionals. I also hope that other gallery directors will take note – with shows like this one, and those that have come before like ‘Soul of a Nation’ at Tate, and 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, also at Somerset House, cultural institutions may sit up and realise the necessity of them. I hope, as a result, that more programmers will write it into their future scripts on a more regular basis.

[caption id="attachment_6162" align="alignleft" width="300"] Horace Ové, ‘John Lennon giving Michael X his hair to auction 1969’. Copyright of the artist[/caption]

This Windrush generation pioneered the Black British art scene, contributing to creating a model for modern multicultural Britain, which has influenced and motivated generations of younger artists in Britain and across the African diaspora. It’s cross-disciplinary and cross-generational, something which has never really been seen before on such a scale.

‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ is on show at Somerset House until September 15, 2019.

Horace Ové, ‘John Lennon giving Michael X his hair to auction 1969’. Copyright of the artist[/caption]

This Windrush generation pioneered the Black British art scene, contributing to creating a model for modern multicultural Britain, which has influenced and motivated generations of younger artists in Britain and across the African diaspora. It’s cross-disciplinary and cross-generational, something which has never really been seen before on such a scale.

‘Get Up, Stand Up Now’ is on show at Somerset House until September 15, 2019.