How do we breathe in a country that does not accept us?

In recent years, several young artists of Gambian heritage have risen to prominence in the UK. As an external curator at the British Library, I have been working closely with the work of one of these artists, Khadija Saye. Saye, a talented visual artist, had received major accolades and had had her work exhibited in the Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, before she and her mother, Mary Ajaoi Augustus Mendy, tragically died in the Grenfell Fire in June of the same year. Some of Saye’s peers include BBC Sound award winning rapper Pa Salieu, award winning poet Sophia Thakur, and award winning cultural producer Ibrahim Cissé. I connected with these young artists through the Mboka Festival of Arts, Culture and Sport in 2021, a space in which we nurture intergenerational and Pan-African exchanges. They affirm and demonstrate through their work that it is their culture and heritage that keeps them grounded and it was this quality that emerged strongly as I curated Saye’s work with British Library curator Marion Wallace in the forthcoming exhibition of her photographs.

These young Africans of dual and triple heritage disrupt and challenge dynamics of power, while also astutely subverting and controlling those same dynamics. As Pa Salieu said in a conversation with Sophia Thakur last month, ‘Our generation is stubborn. Stubborn is not a bad thing if you know what you want to do.’ And in Saye’s prophetic words, from a BBC Britain’s New Voices interview in September 2017, ‘I feel if I can do it, all my friends can do it. I say if you don’t see yourself represented, I think you can do it.’

By centering Khadija Saye’s work, we can bring into focus the similar and varying ways in which these artists dealt with and continue to deal with the racist and anti-migrant power dynamics lived through daily in British society. Saye’s exhibition title: ‘Khadija Saye: in this space we breathe’ could be another way of saying: How do we breathe in a country that does not accept us? It is important to note that Saye’s title embraces others; despite being self-portraits, her works are far from being just about herself. The ‘we’ in her title could be speaking to other women, her Gambian-British peers, or both as to lean into a space to breathe, is to claim it, and this is what these young artists must do to stand their ground. There are nine images in the exhibition at the British Library, and by focusing on two of them, I aim to show how Saye explores and engages the binaries of traditional and popular culture – cultures that are different parts of herself. An initial reaction to Saye’s work could be that her photographic images appear simple, as there is very little in each one but each object and symbol represented and the way in which she places them in relation to her body, fuses her personality with her accumulated power. Alongside these very careful and deliberate choices, however, she has chosen a photographic process that leaves much of the final image to chance. For this, she relinquishes control to trust in the dynamics of her art. [caption id="attachment_21856" align="aligncenter" width="839"] Andichurai, (Incense pot; usually andi churai), Khadija Saye (2018). Printed by the Estate of Khadija Saye in collaboration with master printer Matthew Rich, Jealous and The Studio of Nicola Green. Courtesy of the Studio of Nicola Green and Jealous. © The Estate of Khadija Saye, London[/caption]

In Andi Churai (Incense pot), attention is drawn to a common Gambian household object found in rooms throughout the compound. The Andi Churai (often spelt as one word, ‘andichurai,’) in this image appears to be a traditional red clay pot decorated with white trim, which would usually be brim-full of compacted burned incense, making it heavy. But Saye holds an empty one to her ear like a seashell which implies that she is listening... to the sea of the Gambian coast? To her ancestors? To their stories? Perhaps she is listening to her mother’s stories, whom we know she was very close to, and by doing so, through this traditional object embraces her culture.

A line from a Sophia Thakur poem re-emphasises the mother-daughter bond. ‘Our faces hold the story of our history/that line of your eyes is your mothers.’ We are reminded not only of the pervasive nature of stories in Gambian culture, seeing in both, Thakur and Saye’s work the significance placed on storytelling and the bonds between women.

As the Andi Churai is a symbol of the home, with its perfumed scent, it also reflects womanhood in The Gambia. Her dual heritage meant that Saye encountered and countered what womanhood meant in both cultures. Her unconventional use of a familiar cultural object playfully reflects all of these possibilities.

Saye uses the object of the lemon to layer meanings, too. Limoŋ (Lemon) reflects Saye's admiration of Beyoncé and her seminal 2016 album Lemonade. In the essay 'The Slay Factor: Beyoncé unleashing the Black Feminine Divine in a blaze of glory' by Melanie C Jones, in The Lemonade Reader, edited by Kinitra D Brooks and Kameelah L Martin, Jones discusses liberated Black women and how they deal with and subvert cultural and sexual hegemony. Saye may have seen in Beyoncé, a woman of African descent who successfully challenges and subverts power dynamics, acknowledging and wielding the power of storytelling in order to control her own narrative. We can relate this back to her title and see Beyoncé as a woman who claims space. Although lemons in The Gambia are seen as a Western fruit, locally, they also imply protection from evil spirits, and cleansing, again striking a chord which intertwines traditional and modern cultural references.

[caption id="attachment_21857" align="aligncenter" width="839"]

Andichurai, (Incense pot; usually andi churai), Khadija Saye (2018). Printed by the Estate of Khadija Saye in collaboration with master printer Matthew Rich, Jealous and The Studio of Nicola Green. Courtesy of the Studio of Nicola Green and Jealous. © The Estate of Khadija Saye, London[/caption]

In Andi Churai (Incense pot), attention is drawn to a common Gambian household object found in rooms throughout the compound. The Andi Churai (often spelt as one word, ‘andichurai,’) in this image appears to be a traditional red clay pot decorated with white trim, which would usually be brim-full of compacted burned incense, making it heavy. But Saye holds an empty one to her ear like a seashell which implies that she is listening... to the sea of the Gambian coast? To her ancestors? To their stories? Perhaps she is listening to her mother’s stories, whom we know she was very close to, and by doing so, through this traditional object embraces her culture.

A line from a Sophia Thakur poem re-emphasises the mother-daughter bond. ‘Our faces hold the story of our history/that line of your eyes is your mothers.’ We are reminded not only of the pervasive nature of stories in Gambian culture, seeing in both, Thakur and Saye’s work the significance placed on storytelling and the bonds between women.

As the Andi Churai is a symbol of the home, with its perfumed scent, it also reflects womanhood in The Gambia. Her dual heritage meant that Saye encountered and countered what womanhood meant in both cultures. Her unconventional use of a familiar cultural object playfully reflects all of these possibilities.

Saye uses the object of the lemon to layer meanings, too. Limoŋ (Lemon) reflects Saye's admiration of Beyoncé and her seminal 2016 album Lemonade. In the essay 'The Slay Factor: Beyoncé unleashing the Black Feminine Divine in a blaze of glory' by Melanie C Jones, in The Lemonade Reader, edited by Kinitra D Brooks and Kameelah L Martin, Jones discusses liberated Black women and how they deal with and subvert cultural and sexual hegemony. Saye may have seen in Beyoncé, a woman of African descent who successfully challenges and subverts power dynamics, acknowledging and wielding the power of storytelling in order to control her own narrative. We can relate this back to her title and see Beyoncé as a woman who claims space. Although lemons in The Gambia are seen as a Western fruit, locally, they also imply protection from evil spirits, and cleansing, again striking a chord which intertwines traditional and modern cultural references.

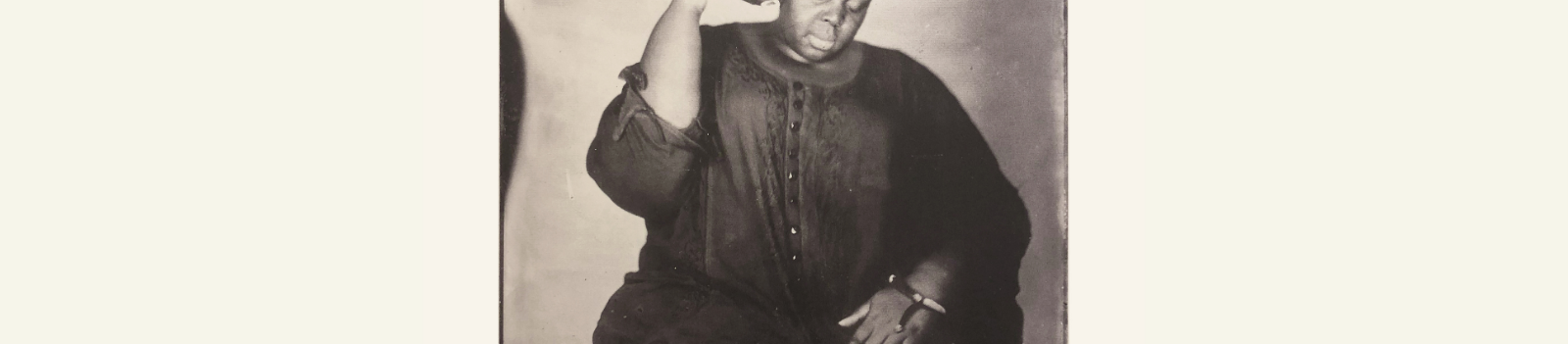

[caption id="attachment_21857" align="aligncenter" width="839"] Limoŋ (Lemon), Khadija Saye (2018).

Limoŋ (Lemon), Khadija Saye (2018).Printed by the Estate of Khadija Saye in collaboration with master printer Matthew Rich, Jealous and The Studio of Nicola Green. Courtesy of the Studio of Nicola Green and Jealous. © The Estate of Khadija Saye, London[/caption] Other strong themes that can be found in Saye’s work are those of faith, spirituality and femininity which she approached with a sense of ambiguity. That she was able to do so informs us that her confidence in her artwork was becoming stronger, enabling her to challenge traumas she had suffered. Saye’s aim to balance her Gambian and her British culture in her own way, which her observations of womanhood and her attention to storytelling in these two pieces show, is apparent throughout all of her artwork exhibited. Cissé spoke to this balancing act as well. He found that in moving from France where he was born, to the UK, there was an expectation that he must select one identity or the other. His work resists this, whilst he acknowledges and plays with at least two identities; Thakur adds Indian and Sri Lankan to hers and holds space in her art for all of these aspects of her story. In their work, we get the sense that these artists do not want to be told how and when their identities should be used — they are turning their identities into positive double consciousness strategies, fighting against oppressive cultural expectations or as Cissé calls it, the ‘miswiring’ that is forced on them, insisting that they accept one history, identity, and exclude all others. These artists are also conscious that they have the opportunity to speak for those ancestors who were not allowed to speak or did not have the opportunity to do so. They now take those opportunities and use them on behalf of those who came before them even as they push the boundaries of the space they are allowed to take up in twenty-first century Britain. ‘We are our ancestors wildest dreams,’ says Pa Salieu. From one of the smallest countries in Africa we witness an explosion of some of the biggest and wisest talent to break through this decade in the UK. Although Khadija Saye is not with us to witness this moment, her work is a fantastic legacy that represents this talent. As she said, it opens the door for the next generation. They all give us hope for the future. Khadija Saye: in this space we breathe is at the British Library until 08 August 2021 Free, but advance booking necessary: https://www.bl.uk/events/khadija-saye. Online version here: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2021/02/khadija-saye.html Digital subsrcibers, or readers with institutional access, can read ‘Grenfell, Race, Remembrance’ by Claire Launchbury in Wasafiri 105 Kadija Sesay is the external curator for the Khadija Saye exhibition. As a literary activist, she is co-founder of Mboka Festival of Arts Culture and Sport in The Gambia. She is the publications Manager for Inscribe/Peepal Tree Press and has edited several anthologies by writers of African and Asian descent. She has also published a poetry collection, Irki, and received a 2020 Society of Authors Grant to work on her next collection. Kadija is currently a scholarship PhD candidate at Brighton University, researching Black British Publishers and Pan-Africanism and received a 2019 Kluge Fellowship to research at The Library of Congress.