12 May 2020

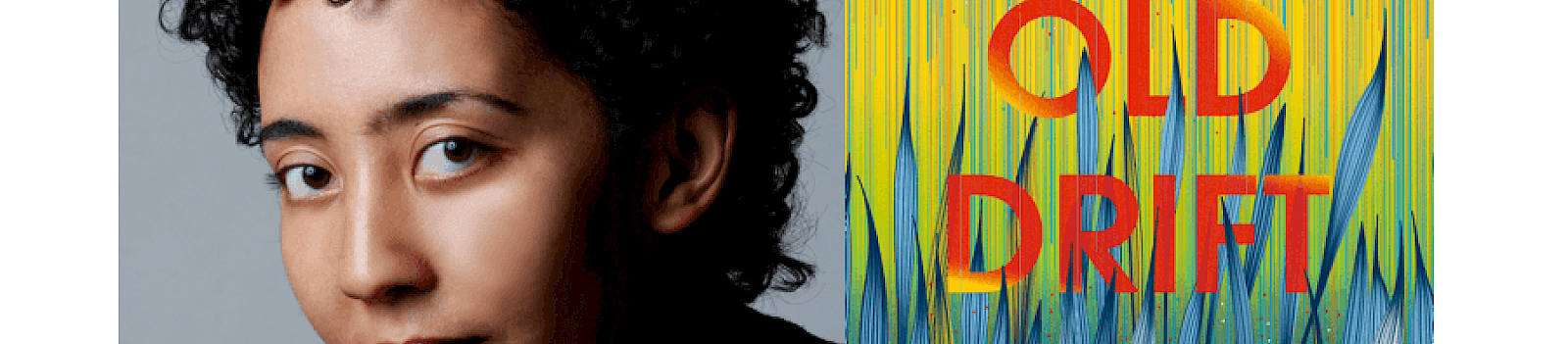

'I often think in threes': Namwali Serpell on the 'Great Zambian Novel'

High praise – ‘Dickensian’, ‘A worthy heir to Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude’ – and a prize considered a literary rite of passage – the Caine Prize for African Writing, or ‘Africa’s Booker’ – preceded the arrival of Zambian writer Namwali Serpell’s doorstopper debut, The Old Drift (2019). Serpell, who split her Caine Prize winnings with her fellow shortlistees in 2015, in an ‘act of mutiny’, was, by then, already a rule-breaker. Her epic novel, at just under 600 pages, is home to three generations of three families, mosquitoes, drones, a woman covered in hair and another woman who cannot stop crying. It is historical and science fiction, magical realism and Afrofuturism. It is the Zambia of the past, present and future.

Sana Goyal for Wasafiri: Shall we begin by talking about the beginnings of the book for you — the origin story of The Old Drift? You talk a lot about chance and chain effects, fate and fortune, and butterfly effects, but it’s also a very deliberately and formally structured book. There’s a three-by-three format – three generations of three families – and while the majority of your protagonists are women, not all are. It feels closely structured, but there’s a lot that’s open too.

Namwali Serpell: That nicely characterises the way that I think in general, which is highly structured with a great deal of internal variation and rambling and wandering. It’s how I work as a literary critic as well. I often think in threes and in structural terms. For the book, it’s interesting to think about the origin story as being both a matter of chance and a matter of highly schematised structure, because I was first writing it in the context of a creative writing course as an undergraduate around 2000/2001. I was developing this story out of thin air. It wasn’t really inspired by only one thing.

The character that came first to me was Matha Mwambwa – who had a different name at that time because I didn’t know about the space programme – and she was crying all the time because her heart was broken. And I knew that her daughter, in response, would not cry – at all – and would be very cynical about love. And I knew that Sylvia’s son was going to respond in opposition to his mother — by being romantic, but about science. So I had this lineage conceived already when the novel was first born. So it was born multigenerational. I read [Zadie Smith’s] White Teeth around that time, I read [Gabriel García Márquez’s] One Hundred Years of Solitude — and I started thinking about families, multiple families, and how they would intersect. And somewhere in the early 2000s, when I was in graduate school, the schematic idea of having three families – with what I was calling at that time ‘a cycling of unwitting retribution’ between them – came into being. So, The Old Drift came into this structure over time.

And you wrote this book over a really long time — going back to your undergraduate years, when you were likely writing in short bursts. I wonder if we can talk about the space of stories – the overall structure – because when reading, I got the impression that these were individual stories of individual characters against and alongside a larger story. Can you talk about space in terms of plotting small – or thinking small, imagining small – and then transforming that into a nearly 600-page novel?

Jennifer Makumbi described it as ‘a series of snap- shots or vignettes’, and that characterises the way that I zoom in to a local situation for a period of time – usually a few years of a person’s life – and then shift to another character to look at another piece of time. So I think some of it is about the dilation and contraction of time that is available in the novel form. I really enjoyed the ability to pause and linger over a day for some of the characters, but then also jump over ten years or twenty years if I needed to.

That’s something I learned – or felt more comfortable doing – after teaching Jane Eyre for the second or third time. There’s one chapter about a day — and she spends a long time, the most pages, on about ten minutes of that day. And everything else – a walk all the way to the post office and back, her whole morning hike – is told in a sentence or two. And I thought this capacity of the novel to expand and contract whenever it wants to is a really lovely tool that’s at my disposal.

In terms of space, I did want the novel to be Lusaka-based. That original story – about Matha and Sylvia and Jacob – starts off in Lusaka. Most of the earliest stuff I wrote was set in Zambia. The chapters that are in England, in India, in Italy, I wrote later. I don’t know why that is. But thinking of Lusaka as a city made up of people from all these different countries was another way in which I could construct space in both a compact way and a very dilatory, spread-out way.

There are some reading aids you provide and others that you don’t. There’s a family tree, but there’s no glossary. You write about this in your essay, ‘Glossing Africa’. In the novel, you leave all the non-English words untranslated, but italicised. I’m thinking of the questions this essay raises, ‘To gloss, or not to gloss?’ and ‘To italicise, or not to italicise?’ – to explain, or not to explain – and whether you feel any responsibility to do that for your reader.

I don’t feel responsible for explaining aspects of Zambian culture to non-Zambians. So there are certain words and concepts and, I don’t know, cultural dross, in some sense, that are spread all over the novel. I was really pleased when I got a review from the Lusaka Times, where the reviewer said something like, ‘This is a book for Zambians but it’s also a book for the world.’ And they gave examples of very Zambia-specific things in the book. That really touched my heart because that’s exactly what I wanted: for there to be these little pieces of language or reference that, if you’re from Zambia, if you’re from Lusaka specifically, will sort of gleam, but if you’re not, won’t distract you too much. Some of these are visible because they’re italicised, and some of them aren’t because they’re cultural phenomena that are not specifically tied to language. I was really interested in that doubleness and layeredness that’s possible in the writing.

I still feel a bit ambivalent about the question of italicisation. I’m not sure. But it was sort of taken out of my hands because I had published a few pieces of the novel beforehand, and those publishing venues had italicised the words, and I hadn’t really thought much about whether I wanted them to be back then. So it felt like it didn’t make sense to suddenly unitalicise them. But I did want it to be clear that any non-English words would be italicised – so any French, any Shona, any Italian, any Telugu would also be italicised – that it was about visually marking linguistic hybridity on the page without necessarily spelling it out or translating it.