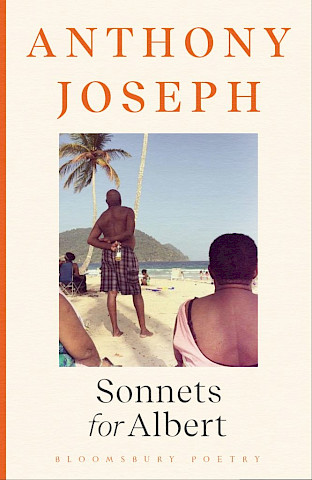

Meditations: Fahad Al-Amoudi on Anthony Joseph's 'Sonnets for Albert'

Wasafiri’s ‘Meditations’ is a new series that features creative and personal responses to new literature, asking writers to seek connections with themselves, their own work, and the text they’re reading. Lying between criticism and life writing, each ‘Meditation’ offers a unique angle to view the writer and the reader, and the world around them. In this instalment, Fahad Al-Amoudi responds to Anthony Joseph's latest collection, Sonnets for Albert, exploring the themes of memory, absence, and the role of the father, accompanied by an extracted poem from the collection.

The sonnet is an easily recognisable form. In its simplest structure, it is a ‘small square poem’ (Don Paterson, 101 Sonnets) similar to a mathematical bracket. A space to solve or account for a problem. The sonnet has all the things we are told poetry should have: music, memorability, scaffolding, an innate ability to tell a story. It is the vestments of Shakespeare, Petrarch, Yeats, Frost. In matters of desire or annihilation, the sonnet is both the question and the answer.

*

Louise Glück once wrote: ‘We see the world once, in childhood / the rest is memory’. As children, there are many different ways we can ‘read’ the world around us. The ‘visible’ – and I mean that in the broadest sense of the word – realm is a script that helps us bridge the gap between what is spoken and what is written.

*

The problem is vision.

*

In Sonnets for Albert, the poet is trying to find his largely absent father. ‘Tall jungle’; ‘appeared through curtains’; the brim of a sailor’s cap covering one eye; fingering through his jewellery. Everything about the poet’s father is veiled, or encrypted in performance. The absent father leaves clues. The wind doesn’t blow for months. The Hathaway record skips. The myth of him grows, and the rhythms of absence become familiar. The sonnet becomes the poet’s key to seeing.

*

Alongside the poems sit images taken by the poet of his father. In one photo, the father’s hand obscures the sun at dusk. Our eyes tell us the father is larger than a star even if our memory tells us this cannot be true. In the poem ‘Jogie Road’, the poet looks up at his father, bloodied like sunset, mining an unreliable memory to make sense of his own conflicted feelings. The relationship between the images and poems is self-ironising. They give the father a new form — a language that is usually designed to validate or challenge the written word. Instead, they obscure the father even more. How do we account for this?

*

The interpreter of the photograph is not built into the camera (‘Visual Language from the Verbal Model’, Colin Murray Turbayne). As secondary school students, we are taught how to identify a poem. Is it a sonnet, elegy, ode? The checklist usually reads: does the poem have fourteen lines? Is the poem in iambic pentameter? Is there a turn somewhere towards the end of the poem? Does the poem have something to say about love? This mode of teaching makes use of our least reliable senses and reinforces a subject-object relationship between the reader and the poem. Do we see the poet’s father, or indeed the poem, as something which needs to be ‘unlocked’? Anthony Joseph’s sonnets are a tool to love his father. But love is rarely stable. Leaden with emotion, some lines spill over to the next, creating sixteen-line sonnets, double sonnets and variations of them. Others have the appearance of a sonnet crown, threatening rigidity before falling away. Sometimes these kinds of poems are called ‘near sonnets’, as if there is a need to codify what challenges existing forms.

*

In Calvino’s posthumously published Harvard lectures, he posits that ‘lightness’ is the function of language. In his analogies, the real world is a Gorgon’s head whose inexorable gaze paralyses us, and so the job of writing is to translate weight into something transmissible and effortless. The metaphor of writing as ‘a magnetic field’ is easily transferable to Joseph’s sonnets, which sometimes resemble rites of masculinity, or folkloric symbols of boyhood. Grief, one of the real world’s many plagues, burdens language with cliché. Myth, like Perseus’ winged sandals, allows us to glide over painful experiences and memories with ‘lightness’, telling a story implicit in images. Occasionally, but perhaps not often enough, Joseph finds these images — ‘a fire between three stones’ (The Sweet Yard’) ‘the small birds/ within the emptiness of the cricket field.’ (‘Shame’)

*

The problem is memory.

*

Text is a social space, where everyone you have ever read is watching over your shoulder. Or, in the words of billy woods, ‘the gang’s all here.’ Something that writers are often taught to do early in their career is to create a ‘tree’ of their inspirations. Part of this exercise is to do with the process of voice but it also helps to understand that all writing is reading, and all reading is re-reading, re-configuring, rendering again. Just as you have blood, you have a literary inheritance, and inheritance is itself a kind of form. How to be a father. How to be a son. In Seamus Heaney’s ‘Digging’, the poet’s father digs his own grave searching for his father, who is also digging his own grave. In writing this discovery, Heaney grapples with a rejection of tradition, and the language of inheritance is re-calibrated from the ‘spade’ to the ‘pen’. Heaney, as Joseph’s aunt might say, is doing ‘the work of generations’.

*

Basic semiotics tell us that the written word ‘father’, the auditory sound ˈfɑːðə, and a photograph of the poet’s father are all symbols that denote what we might call the ‘real object’. In the case of the absent father, the poet uses the language of metonymy and in doing so Albert becomes fragmented, shrinking into symbols and gestures in the text and in the mind of the reader. Instead of saying ‘pops’ he says ‘ring’, instead of ‘dad’ he says ‘stones’, instead of ‘father’ he says nothing.

*

Language is a metaphor for the body. The body is where memory is stored. The sonnet is where the body makes itself known to another. The poems in Sonnets for Albert are mostly anecdotal. The poet remembers his late father, hoping that in death his father will become knowable. In remembering, the poet is giving away parts of himself rather than his father, as he might have hoped. John Berger describes spoken language as ‘a body… whose visceral functions are linguistic.’ (Confabulations). The poet’s father is a text, and in reading ‘through’ him we can reach those non-verbal expressions that Joseph often titles his poems — ‘Shame’, ‘Breath’, ‘Light’.

*

The poet expects nothing of the absent father, so long as the absent father expects nothing of himself. This is what is known in maths as a ‘conditional equation’. The variable here is not the absent father but the poet. Joseph’s presence in the sonnets moves in several valences, like waves retreating from/climbing up the shore. By contrast, Albert finds a kind of equilibrium. Albert the chef equals Albert the taxi driver equals Albert the carpenter equals Albert the husband equals Albert the middle manager equals Albert the father. Perhaps this is the square root of elegy? ‘Each man sinks with the sum of their deeds’ (woods, ‘Epilogue’ from Rome). The collection feels very much like a private catalogue of grief. The poems are approached with uncertainty, things are left unsaid, and the text reflects this loss in a kind of dissociation. Through anger, shame, indifference, admiration and regret, Joseph feels himself estranged from his father’s body, seemingly unable to account for the gaps between memory, vision, and the self.

*

‘Don’t make a promise you can’t keep / don’t make a keepsake out of grief.’

– billy woods on ‘Sir Benni Miles’ from Haram (Armand Hammer)

*

One of my earliest memories of my father was in the flat I grew up in alone with my mother. I would have been seven years old. My mother’s parents were visiting while she was in hospital, where later that year she would pass away. ‘Baba’, as I was told I should call him, was there for his annual check in. It was March in London, so the sky was smudged with graphite. Rain shook at the window through a sieve. My father wore a Gillet over his jacket and a pair of sunglasses indoors. One painting of a sunflower lit the room. Grandma took me to the kitchen for a snack. I pulled at the edge of her wool jumper and she turned back from the cupboard. ‘Who is that man in the living room?’ ‘Who?’ ‘The man on the sofa.’ ‘Fahad, that is your father.’

Shame II

I was recording in St Anns and had one day free. So I told my father I'd be back in December; and he said, 'December? No, I want to see my son, Tony; we in August.' Everything is symbolic in literature. The dust at dry noon in Sam Boucaud, the small birds within the emptiness of the cricket field. Heat burning water into sound; tall jungle. My father appeared through curtains, thin with eyes that now saw past the limits of ours. The impish swirl of his laughter was gone. In the photographs I took that afternoon he seemed to be leaning away, leaning as if from life, from love, in shame. 'Shame II' appears in Anthony Joseph's Sonnets for Albert, published in 2022 by Bloomsbury.

Fahad Al-Amoudi is a poet and editor of Ethiopian and Yemeni heritage based in London. His work is published in Poetry London, bath magg and Butcher’s Dog. He is the winner of The White Review Poets Prize 2022 and has been shortlisted for the Brunel International African Poets Prize. He is an Obsidian alumnus, member of Malika’s Poetry Kitchen and is the Reviews Editor for Magma. Cover image by Marco Bianchetti on Unsplash