22 March 2017

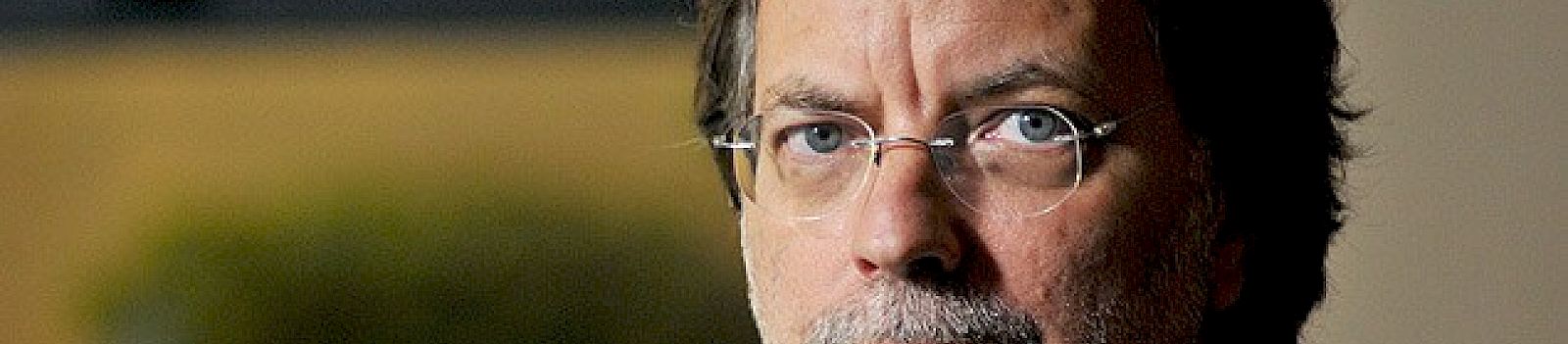

Mia Couto talks to Brian Chikwava

Mia Couto rarely comes to London. He is here for the Rolex Mentor & Protégé Arts Initiative. For a writer with quite some silverware to his name it is not surprising that when I arrive at Sofitel London St James it looks like he is already well into what could be a brutalising press and broadcast schedule today.

I am five minutes early and he is in the middle of another interview, I am informed by his PR minders. The four of us stand in the hotel lobby, making anxious small talk. Clock checking.

When my turn comes I am led to the hotel bar where Couto is sat at the corner.

Given Mozambique and Zimbabwe’s history I think I should address him as Comrade Couto, I joke. He seems amiable enough.

As we take our seats he informs me that he has been to Zimbabwe a few times while working on the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. Outside writing he is also an environmental biologist.

I wonder what kind of an interviewee he will be. His fiction suggests a deep dreamer re-imagining contemporary Mozambique and crossing it with archetypal forms that predate western cultural hegemony. The results are often rewarding, hinting at possible new ways of looking.

In his essay, Languages We Don’t Know We Know he writes:

“… the languages we know — and even those we are not aware that we knew — are multiple and not always possible to grasp with the rationalist logic that governs our conscious minds. Something exists that escapes norms and codes. This elusive dimension is what fascinates me as a writer.”

If this is also informs his approach in conversation, then the allotted 45 minutes is not going to be enough.

We talk about the Rolex Mentor & Protégé Arts Initiative. He is eager to divert attention from himself and towards this project, especially the young Brazilian writer Julián Fuks. He is mentoring Fuks. The images of Fuks that I have seen on mentoring initiative’s website show a man with the vast beard of a revolutionary Marxist; he should be motorcycling across Latin America starting revolutions and mentoring revolutionary youths.

Since Couto is ex FRELIMO, one may as well start with the subject of the intertwined histories of liberation movements of southern Africa. It is that past that enabled him to write a letter to the South African president, Jacob Zuma, addressing him in personal terms, following the horrific xenophobic attacks in South Africa in 2015.

“In the new world order where people that you once addressed as Comrade are now Mr(s)/Ms and wear Armani suits, are African solidarity and a shared history of struggle still meaningful ways of relating to other Africans? Is that language still viable?”

“When I see that songs, poems from the younger generation still claim Africa as a whole, as the big mother I realise that there is a need for a common identity,” he says. “We are still inspired by the idea of being Africans.”

His style is expansive and explorative; he talks around the question from a high altitude, thinks his way through before deciding where to land. Having talked up the endurance of pan-African solidarity and noted the constructed nature of our national identities he finally deploys his landing gear: at least regarding Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa, “we’re so far away than we have ever been before.” There is little cultural exchange “We don’t know what is happening in South Africa or Zimbabwe. We know more from what is happening in the US… It’s not the language but a lack of interest and political desire.”

And what about the language question that shows no sign of disappearing from discourses about African literature?

“Your fiction has been celebrated for its innovative use of Portuguese,” I begin.

“That’s just what they says,” he chips in self-effacingly.

In a speech that he gave about Jorge Amado in Brazil, 2008, he also allies himself with the reinvention of Portuguese to make it a language that fully articulates the lived experience of its speakers in Brazil and Africa. His position seems close to China Achebe who said ’Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English, for we intend to do unheard of things with it.’

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has a different take: indigenous languages must be the primary means of cultural production.

“For a lot of young writers starting out, all of this can be petrifying. What your advice?”

“Nobody should impose the language that you use,” he says. “The English that is spoken in Zimbabwe is not anymore the English of England.”

He notes the absence of institutional and infrastructural support for indigenous languages. Someone writing in an indigenous language starts from a disadvantaged position, he says, compared to someone writing in the official language, i.e. Portuguese, French or English in much of sub Saharan Africa. “This is the issue. We should not have this problem.”

He also agrees with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in many respects “but you can not say this is more correct or not correct.”

“In your essay collection, Pensativities, you address a number of issues facing Mozambique, from the economic, the cultural and right through to the environmental. Beyond Mozambique or Africa, the world is currently in a state of flux; we have Trump’s USA, Brexiteering UK and in southern Africa, violent outbreaks of xenophobia. Is it time for languages we don’t know we know?”

“I think what’s happening now is the result of a construction that is even prior to language. It is fear.”

He talks around the question, touching on mass fear around the globe, the manipulation of people – easier now that old social security nets are vanishing – and epidemic levels of loneliness in atomised societies. This time it looks like he will not land but he does.

“This is not the answer but I think we preserve, in Africa, a sense of the importance of telling stories. You become human because of story telling… We need a new narrative that is enchanting.” The re-enchantment of our relationships is what we need, he emphasises. Then he looks down, head almost shaking, and says: “This is very naïve of me!” We laugh.

“In today’s global context, why should anyone care about what Africa has to say when there is Mandarin to learn and containerfuls of iPhones are waiting to be shipped from Chinese factories?”

He used to be dismissive of Europeans visiting Africa and talking about sensing something different about Africa. He thought they were exoticising. Lately he has been rethinking that.

People do seem to “come away with something they can not give a name to,” he says. The time sensibility is different in Africa he thinks. After highlighting African cultures’ comfort with silent spaces, he is now talking mindfulness in all but name.

“Maybe Africa still can say something.”

He sees Africa as possibly providing a space in which to reconsider our values and rethink the profit motive as the basis of the modern world. It is a radical proposal, advocating values that consumption capitalism has neither eyes nor metrics.

“In Confessions of The Lioness, the village in which the story is set is named Kulumani, which means ‘talk’ or ‘speak out.’ You are championing women’s causes. But on a continent where books are often a luxury, how does a writer overcome the contradiction caused by the povo: they have a lot to gain from participating in these discourses but often can not afford to engage in them? How do we avoid the trap of ending up in a situation where it’s just the literati talking to itself?”

On this one he speaks for himself. He tries to distribute his work in as many forms as possible. That is why he has had some of his work translated into indigenous languages and performed as plays for theatre and radio broadcast. We are in uncomfortable territory now.

Is he is in any way influenced by Paolo Friere’s Pedagogy of The Oppressed? He is about to give a detailed answer but his minder steps in to whisk him off to the BBC studios.

-

Brian Chikwava is a London-based Zimbabwean writer.

Brian Chikwava is a London-based Zimbabwean writer.

Brian Chikwava is a London-based Zimbabwean writer.

Brian Chikwava is a London-based Zimbabwean writer.