5 December 2018

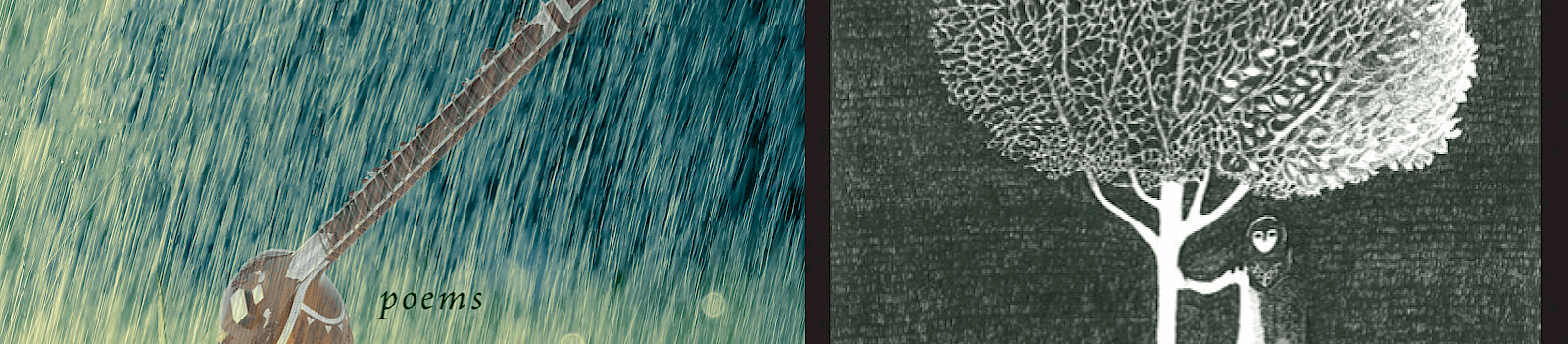

Review: Luck is the Hook by Imtiaz Dharker and Monsoon on the Fingers of God by Sasenarine Persaud

Rain soaks the pages of these two collections, Monsoon on the Fingers of God by Sasenarine Persaud (Mawenzi House: 2018), and Imtiaz Dharker’s Luck is the Hook (Bloodaxe Books: 2018). Dharker writes of a lifetime in Glasgow, while Persaud’s collection is generally located (aside from a few fiercely political studies of warfare which fly him away), in Edinburgh during the time of the referendum. In the Scottish climate, these poets cannot help but to succumb to a drizzly, socio-political pastoral where the landscape transmutes and bears personal meaning. Dharker gives us images of love in a cold place, the insular tenderness it engenders, in Thaw (p22):

Dark-too-soon, untimely as it is, Takes us straight to bed, throws back The sheet and draws us in to thaw Your frozen feet between my feet.

In Persaud, a territorial battle is played out across a constantly drenched vista. ‘Silence from your side/ of our pond’ (‘Through Waverley’, p17), scattering a psychodrama across the landscape (‘We always have unfinished business—/ Your mountain or mine—’’ (Cove Park, p6)), including a rainy footpath which he and someone walk up and down in a leaving that never ends:4 hold my arm down the wet close and we reach the bottom too quickly

beneath breath, beneath Krishna clouds and Goberdhan mountain, hold my hand hold my heart and never let me go (Through Waverley, p10)

Scotland becomes a mirror in which Persaud can see his past homes; a coffee shop chain bears a president’s name; rain becomes the titular monsoon, and Hindu gods move the skies; Kali moves the Scottish tongues around him. In this, the work grasps for a universalism that exceeds the trappings of identity. This final phrase, ‘never let me go’, returns like a chorus throughout, refusing the distance of articulation. In ‘Exiles: Americans in Edinburgh’: “Yours Britannic, our liver Scoti, yours Sanskrit/ Except when we touch arms/ And our eyes sing: never let me go, never let me go.” (p26) He draws attention to details that reintroduce uncertainty into the political landscape of identity: ‘A tiny red cross on a white face engraved in India/ Ink: England.’ (‘England’, p47) Although he finds himself a foreigner in this land, there are moments of ‘Confluence’ (p51), as one poem is titled, where apart rivers flow together and commonalities emerge. ‘My bonnie lies over the sea, we sang/ in a colonial childhood, who the colonizer?’ In this way, he considers Scotland also as a colonised land, with its own point of proud cultural outrage, at odds with the language they speak in. This national pride irks Persaud ‘you have a language, still the Gaelic/ and this unenough’ (‘Through Waverley Place, p22). By considering how national identity is always a collage of domination, he refutes the sanctity of Scottish history and the Gaelic language. Images of the mouth give way to a culinary semiology through which he tests the mutability of culture; ‘maybe samosas weren’t meant to be shared,’ (p25) he writes, and considers the difficulties and merits of curried haggis (p16). For both poets, technology intrudes on the pastoral, but with different effects. Dharker finds technology to be at odds with nature. In ‘the garden gnomes are on their mobile phones’ (p107), she writes, ‘The gnomes are busy/ watching Game of Thrones […] For the basil, time moves in slow motion/ And the gnomes are a passing blur.’ This, to me, is a clumsy critique which does not account for the seamless way technology infiltrates modern lives and emotions. At this point, “what if phones, but too much” is a cliché, a meme; it draws a false dichotomy between consumption of technology and participation in the world. There is something to be said about people increasingly declining to move in favour of watching people move on screens. But the internet also provides a constant source of information. Technology may have transformed our experience of the world, but it is often just another dimension to experiences that never change. I can photograph a flower, and also smell it; I can ask Reddit to illuminate the flower’s origins, and write a poem in my notes. Persaud tech-pastoral is more successful in capturing this symbiosis: ‘Smartphone torchapps illuminationg the asphalt night./ Look out for cowpats! Someone yells too late.’ (‘Through Waverley’, p23) Screens can hold poetry, too- ‘Our limbs on paper, on keyboard our/ Hearts and soul’ (24). As an Iranian raised in Liverpool, a Scouse Iranian, both collections strike with hot spears of familiarity that land. They ignite memories of my life, the years I’ve spent learning to speak in the voice of a city who does not recognise me by sight as one of its own. Persaud captures the anguish of cultural solitude, the uselessness of begging to see anything like yourself looking back at you. ‘I can’t pretend to sing a raga/ to your island rain today–give me sun/ give me sun give me sun’ (59). The opening poem of Dharker’s collection epitomises how the immigrant is caught up in a grindstone between two identities which each efface the other in order to fully exist, and how this conflict is carried in language. She describes her father’s pride in pronouncing ‘loch’ and ‘hen’ correctly, ‘with an och not an ock, to speak/ proper Glaswegian like a true-born Scot’ (‘Chaudhri Sher Mobarik looks at the loch’, p10). But underpinning this performance of assimilation is an unacknowledged cultural resource which springs from elsewhere: ‘and he makes the right sound at the back/ of the throat because he can say khush and khwab and khamosh’. This finds a summary in Persaud’s lines: ‘We want your head and heart and soul/ And body – whole we offer but cannot give’ (‘Through Waverley’, p12). Assimilation is an act of surrender which cannot succeed, an apology that cannot follow through on its promise. For Dharker, who was raised in Scotland, the cultural fracture runs deep and creates insurmountable silences, so that life takes the form of a murky water and words are the surface. Threaded through her collection is an obsession with poetry, language, and their limits. ‘If you have come to write the hurt/ out of your heart, to take the ache/ and heal it with words, leave now./ no scrabbling in dead poets’ bins can turn gone into come or become.’ (This Tide of Humber, p115) Dharker’s writing laments its own , as though she is screaming from inside a well in vain hope of being heard. ‘My thin voice speaks/ from a drowning world’ she writes in Six Rings (p51). Poetry is only ‘An arm or a leg or a hip/ Heave out from under the sheet./ The lifted mud is only a hint/ Of the lost land beneath.’ (This Tide of Humber, p116). Her words become ghosts haunting our ‘living world… you stop/ as if you have heard, and say, Listen.’ (‘Beak’, p48) ‘You hear something, but far,/ Like a ghost with no throat,/ Like a shadow of words under water.’ (‘Six Rings’, p51) Both poets sometimes consider the vulgarity of this act of screaming. For Dharker, we are voyeurs, eavesdroppers seeking gratification in ‘Six Rings’ (p51): ‘Others tune in, taking advantage/ Of the opening, crying over me/ Wailing against the wall of white’. In ‘Through Waverley’, Persaud asks himself:How did you find yourself naked On a cover, in the much praised pages Of a thin volume, your heart raw, vulva aching Publicly more eloquent than any penis Rising like the wind outside on the loch (22)

And indeed, there are moments of ‘Through Waverley’ in which the collocation of the words ‘toe’ and ‘tongue’ suggest a Tarantino-esque penchant – ‘On toes we might hold or touch or tongue’, he writes – the kind of TMI we live for. But in both Persaud and Dharker, the silence of touch speaks gracefully and sincerely. In ‘The Letter’ she writes, ‘If you were here/ I would write my message/ with fingers on your skin.’ (45) These poets make words perform their own limits, show how meaning-making can be too boisterous in its certainty. Persaud does this formally, also; notions come in a pitter-patter, cut off and resumed pages later. His rhythms break away from the English canon, and repurpose its iambs for a cyclical structure built on a non-western sense of music. Meaning is layered through repetition, mimicking the erratic motion of thought in how its themes divert and reprise. The nonlinear nature of perspectives defined by multiplicity is enacted formally in Persaud. But within this, he evokes a mystical humanism that transcends this fracturing effect. ‘The final poem, an homage to Anne Waldman’s ‘Aphabet of Mother Language’, echoes the themes of that exuberant diatribe on the Goddess of language: ‘She is keepertime and spacetime.” (‘If Kali Were a Car’, p100) Through divine intervention the tongue is made from a tool of language into a tool of love, and the anxiety of human context dissipates. ‘This is tomorrow/ and tomorrow and no tomorrow – there is/ no other world and space and time/ no other world, but this and here and now’ (‘Through Waverley, p24). Dharker favours a nascent absurdism over mysticism, but to a similar end. ‘The lurch of too much’ gives way to ‘A stranger’s heart, wiped clean/ Holds on hard to the edge of luck.’ As luck would have it, there are quiet places in any landscape, and miracles of love in every life. In transient moments a wordless, cultureless, human longing dissolves the inventions of language, which politicise and demarcate in favour of a universalism in which identity is suspended. ‘Never let me go’, Persaud repeats. So too in her love poem ‘To have all this’, Dharker writes, ‘snowfall hushes outside/ and the bed is our only country’ (22). These are delicate, comforting collections. ‘Old Loves New Loves’, the opener to Persaud’s collection, doubles as a dedication:For things we could never do the gulf too wide to leap across skins. A child uttering if you drink milk, you will get fair

The formal and stylistic differences between these two collections are obvious. Dharker speaks as an outsider but also a Scottish person, and her words naturally fall into the rhythms of this language. Its more traditional poetic forms, like rhyme, often shape her cadences. By contrast, there is no couplet in sight on the pages of Monsoon on the Fingers of God. Speaking as a traveller, his poetic gaze is erratic and international. For Dharker, however, her local concerns are universal in themselves. She writes openly of her mother, her son, and grief. The poetics which thrusts her work is well summarised in ‘This Tide of Humber’: ‘The smallest window you have ever seen, And through it, shows you all the world’ (p119). What unites these poets is a certain impulse, to seek out between politics and frustrations a wordless love which resolves the cruelty of human solipsism by grace. Luck is the Hook by Imtiaz Dharker Bloodaxe Books, Northumberland, 2018 128pp, ISBN 9781780372181, £12.00 Monsoon on the Fingers of God by Sasenarine Persaud Mawenzi House, Canada, 2018 120pp, ISBN 9781988449319 , $19.95 - Niloo Sharifi is a poet, writer, editor and videographer from Liverpool. Her favourite book is The Little Prince.