19 June 2020

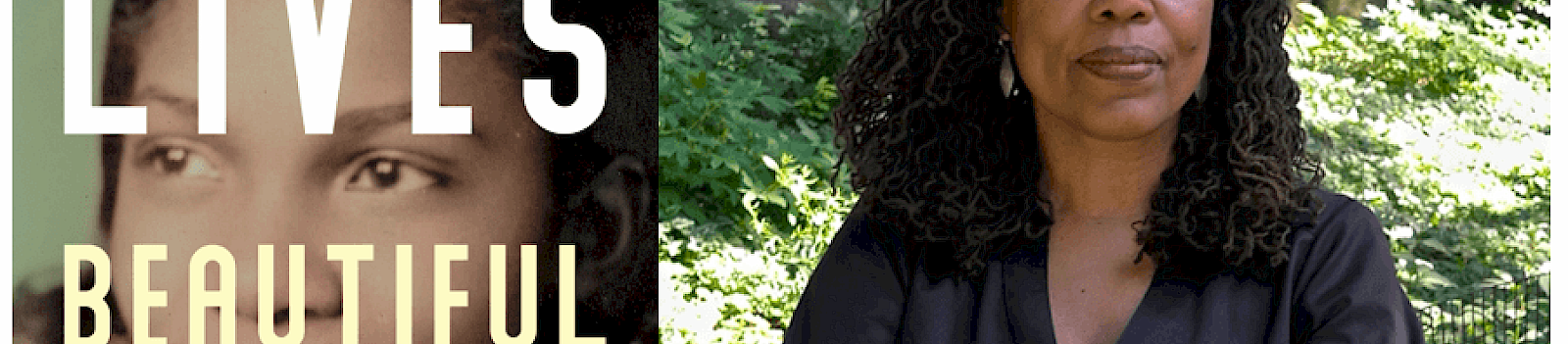

'Soft Liquid Rigour': Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

It is hard to review a book of such gravitas and importance; a text that refuses the boundaries we were meant to exist within. How to honour the soft liquid rigour, the sharp vast tenderness, of a writer like Saidiya Hartman? Or, how might we honour any black woman, in all their loud unlovely nuance and careful wholeness?

The brilliance of Hartman’s work is in its wayward reach throughout the diaspora, its dedication to storying black life in relation to specific histories of transatlantic enslavement. Her 1997 book, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-century America, brought whole discourses into being with her urgent and expansive analysis of humanism, empathy and ‘the encumbrance of freedom’ for black people. You would be hard-pressed to find contemporary radical black thought that is not the inspiration for or confirmation of her literary offerings. Wayward Lives is Hartman’s third book, and commands our attention within the context of the sort of international acclaim that is available to a select group of black people about once every fifteen to twenty years when capitalism and white culture engage black creativity, knowledge and skill in a rare – if only so due to a chronic amnesia – and passionate embrace, a public display of consumption that is sold as affection and keen interest. This raises important questions of how we as black people, living beautiful and wayward and experimental lives, should or will reckon with such work. What does it mean to encounter black life through the whim of dominant white capitalist culture? What of the other(ed) or premature or damned Hartmans that surely can and have existed? How do we resist pedestals formed only of rubble and black Mass?

It could be said that Wayward Lives rewrites or reimagines stories of young black women from the archive of African American migration to the North. But this would obscure the labour; Saidiya Hartman gives black archival life the vigour and fullness and interiority of an intimacy that transforms you, the kind you write feverishly about in your journal so that you might recall it the next time a child asks you what love or heartbreak or ageing feels like. You know these young black women because you have already imagined that the unnamed child in figure twenty-three had a voice and a particular temperament, a preference for the way light fell between leaves and dappled shade and warmth on her face. Wayward Lives introduces you to your always-already embodied self and to speculative visions of a ‘you’ in a different time and circumstance.

There are days when black life is a series of stony absences threaded together by a tearful and raging pre- carity: these are days where the naked sores and swollen contours of a makeshift living bloom in little crevices and you reach for another world. This reckoning with black life beyond and bursting through the blind spots of white vision is precisely the engagement that Hartman’s work prioritises. Whether we are being introduced to a lauded civil rights activist or the speculative life of a footnote in the diary of a white landlady, each character is sanctified and redressed with holistic grace. We are invited to commune with our own limitations, so that the negro in first class who ‘fought like a tiger’ against the ‘two additional men ... required to assist the conductor in ousting her’ (38) pleads you to stop reducing her to something other than just-like-you; we are not used to acknowledging the interior world, the sentient life, of Ida B Wells. Nor are we adept at imagining the twenty-eight-year-old sociologist ‘at the corner of Seventh and Lombard’ who wore ‘a well-cut three piece gray suit, with a gold timepiece nestled in the vest pocket and an elegant cane resting beneath his manicured hands... every inch the dandy’ (86) as Dr W E B Du Bois. There is something fungible about these characters: Shine is every negro man. Every negro girl could be and is way- ward, a whore, a domestic. Beautiful and unrestrained by movement; ‘to yield, to be undone and dispossessed by the force of her desire, and for no other reason than that she wanted to, made Mattie feel vital, untethered’ (62).

Perhaps before we were introduced to Hartman we could have said that her work humanises the hollow bodies that black people are reduced to by white supremacist notions of truth and rigour. But the love – there is no more accurate word – with which she deals with scenes from the tragedy of black archival life does more than the term humanise is capable of relaying. We see in the writings of Helen Parrish and in the photographs of social reformers and sociologists a desire to make Human the Negro, a desire to improve the conditions and characters of these errant black young women. But ‘humanness’ here means a life of servitude and work, a particular set of desires, a fixed path, confinement. Hartman leaves us unsatisfied with the category of human as the ultimate panacea for racial justice. What is it to humanise those who have always been denied humanness? How can one be human when the body is open everywhere, the home and familial ties open too? When children, wives, lovers, mothers, girlfriends can be taken away? When the black private is public, the black private is public risk, the black private is – and is required to be – public knowledge, open to public scrutiny? How can one be human when the black private is owned by the public?

For girls like Mattie, surveying the rolling Atlantic on her travel north, or Mabel boarding a train from Jersey City to Manhattan, or Esther wandering through Harlem, this humanness was not a thing to be aspired to. Instead they sought ‘something else’ (46), they refused these conditions and terms, longed for an ‘otherwise’ (235), they practised treasonous freedom. These minor figures become radical political actors; a chorus that displaces the singular hero who set history in motion; crucial interlocutors of the practice of refusal. Our black being pushes beyond and underneath the very conception of humanity, leaving us breathless and invigorated, renamed without certainty or solution.

In place of the unparalleled importance of our right to ‘Human Rights’, is the insatiable desire for more questioning — for questions as experiments and for experiments as a way and a means for our living. For those of us who turn to the archive seeking comfort, looking for old ways of looking at new things, for redress to our subjugated history — this book is a balm and a pedagogic tool. Wayward Lives is a book that wants you to live.

— Imani Robinson and Ebun Sodipo