The Books That Didn't Make Me by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson

In this piece, Wasafiri’s Writer-in-Residence, Jessica Gaitán Johannesson, interrogates the books that have – and haven’t – shaped her. In the process, Johannesson also explores the connections between writing and activism, and her own complex history with literature, while elegantly deconstructing the idea that the act of reading alone can save the world.

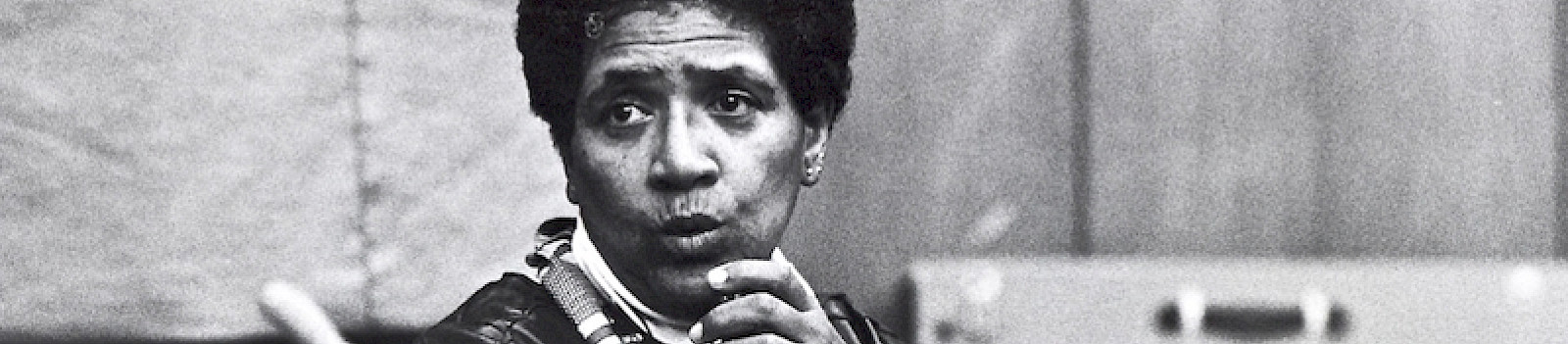

The Book That Made Me Stop Eating Fish or so I thought, at first. It also made me think that its author would be lovely. That he would be in-the-flesh generous and put good things back; an easy laughter, where the dead fish had been. Years later, when I interviewed said author, he attempted to guess my age on stage, unprompted. He also said that he didn’t think about writing — he ‘just wrote’. It’s a good thing that, at this point, I’d stopped eating fish for other reasons (the greater chains of carnage, a shared flat of vegetarians). Pissed off, I might have gone in search of mackerel. The Book That Made Me Come Crawling Back to Poetry also reminds me of its slipperiness, the way it serves. The internet punctuates itself with statements elevating poetry to the status of lifesaver, world-messiah, nobility in florescent light. These quotes are our time’s embroidered prayers above the hearth. ‘Poetry is not a luxury’. In the essay of the same name, Audre Lorde makes the point that poetry is, for women, never an add-on, but the very breath that promises other, fuller ones; less tethered ways of existence. That essay is full of poetry, but crucially, Lorde’s activism was in no way exclusive to her poetry. To name a few of her other endeavours, she co-founded Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, in solidarity with women under apartheid. She was a founding member of Women’s Coalition of St. Croix, a group in support of survivors of partner violence. She spoke at rallies for LGBTQ rights. This work isn’t mentioned as often in biographical notes of Audre Lorde. Does this mean that the activism needs no clarification, no life-story of its own? Or is the activist in ‘she was a writer and activist’ assumed to operate under the umbrella of the writing? Is it, by default, adopted into writing’s noble hereditary line? Seeing the quote made poster, made slogan for poetry-as-activism on a Zuckerberg-owned app, reminds me of why the amalgamating of literature and activism deserves my mistrust. I adore Lorde’s poetry for this. The Book That Made Me Stay Colombian Yesterday was Gabriel García Marquez’s birthday. I flick through my 1983 copy of Cien años de soledad and thank it for my still speaking Spanish. I suck the motherland from its pages and hold it between inflated cheeks, waiting for it to take effect. I read Colombian Spanish so as not to forget; I read to be made more of something that may otherwise run dry. The book is enough to keep me in its company, until I try and speak about queerness, mine and others’, or terror of climate breakdown, in Colombia, in Spanish. A thousand worlds, mine and others’, were never in this book, in a thousand kinds of Colombian Spanish. The Books That Made Me Stop Drinking Coffee (for a while) But Didn’t Make Me an Organiser They caught me as a student, in the west of Sweden, around 2008. The climate crisis was, to me, itself a distant story, a chain of cries and their echoes. In Margaret Atwood’s apocalyptic Maddadam trilogy, slums built from layers of murder exist alongside hermetically sealed communities, preserving privilege within. It all seemed too familiar, said the reviews; these are urgent, such flaring, stark warnings. It didn’t seem familiar enough. Dystopias are hailed for their engagement with climate collapse, yet a dystopia, by definition, is set in the future. The genre is framed not around the here and the real, but the there, and the possible: a suffering that is not yet palpable, meaning yet to be touched by the imagined reader, who (looking up from the book is still safe enough to look down again and keep reading), the reader who is meant to be you. Warnings necessitate the distance of foresight — the lucky stars of ‘soon but (thank god) not yet’. If ‘not yet’ then I still have time to keep reading. Do we wholly discard the writer as seer because today holds brutality enough? Consider the future as seen by some queer writers, by writers of colour and disabled authors, by the many who carry historical oppression into the future as a space in which to make it explode, where explosions are possible precisely because this future has not yet been written. Consider Octavia Butler, N K Jemisin, or Rivers Solomon. Think of writers who say, merely by being in the future: ‘we survived’. Or turn not to the future at all, but to the ecological apocalypse on which we stand; turn to Indigenous writers. Against the racist disinterest of publishing industries, seek them out, and seek beyond the readily available, make the voices you hear too numerous to name. As for the dystopias, I don’t blame those who write them. My fears guide my writing too. But here is my question: if this is future horror, what inaction is still allowed now? What waiting may still be condoned, if it’s not yet that bad? What I ask myself, having read such books, is: whose hurt counts as nightmare enough to be avoided? The Book That Didn’t Give Me a New Language did remind me of the three I always had. When I first read Borderlands/La Frontera, by Gloria Anzaldúa, I let out a trilingual child’s sigh of relief. Come in, the book said, listen to me with every part of your inner ear. In what the queer, Chicana writer calls a ‘forked tongue’, one that interrupts the dominant English with vocabularies of migration, mixed accents, haunting it, there was the possibility for that tongue to renew its surroundings. ‘Poetry is not a luxury’. But it is illumination, Lorde writes: ‘the quality of light by which we scrutinise our lives’, which has a bearing upon ‘the changes which we hope to bring about.’ Language is itself a quality of light, a filter that defines everything and its shadows. Rather than literature as warning of hardship to come, this is writing as a necessary act of liberation; a part, but not all, of Anzaldua’s work as an activist. The Books That Were Going to Make Us Feel Better About Writing Books They were clutched so, so tightly against the writers’ chests that neither the books nor the writers could breathe. I’d gone along to a meeting of writers wanting to Do Something. Something about existential threat, against climate collapse, something for general survival on earth, to do something. Isn’t that what anyone wants their writing to do? Isn’t that something? ‘Thank you’, a writer said, after the lecture about tipping points, likelihood of mass starvation and the possibility of five degrees of warming. ‘But what can we do, as writers?’ And you sit there, half-giggling, half-vomiting into your wine glass, because where does that leave us, other than stuck in the writing? If by Doing Something, we mean only in our capacity as writers, then what is it that we want: to save lives, or to save our lives as writers’? This Book, This Book, oh, this book. It must surely show in the kind of liquid my face produces that I just read this most marvellous, powerful book. It has made me — did I not exist before? The Books We Make ‘Books are a force for good’. ‘Turn to the books’. ‘What would we do without books?’ I hold the book I wrote and try to feel like I made this; like it could bring me, somehow, into being with others. And the paper, the glue, the ink, the wages, the carbon, the shipping, the unregulated retail hours, the who has power and who has much, much less, are all constraints within which any book happens. The claims by those with power that what they have isn’t power at all, the racism and the privilege threatened by its dismantling — this is the foundation upon which my words, about climate collapse and privilege, will be read, traded, consumed. Working as a bookseller, I once had a meeting with a sales representative who said, ‘climate is very on trend’. Soon after, a promotion kit for a novel arrived. The book was about climate collapse. Its promotion material included a plastic water bottle with the book’s tagline printed on the label. This is not the writer’s fault. It is, however, poetry, made luxury, straight into the recycling bin. The Books That Were Meant to Remain Books Apply the sales rep’s attitude to any festering wound, to any story of remote and direct violence. After the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests, Reni-Eddo Lodge became the first Black British author to top the UK bestseller charts. She expressed mixed feelings: ‘the debate on racism is a game to some and I don’t want to play’. The search for what sells can also feel like a game. We do not, will never, win, because any change writing might instigate is beside the point from the perspective of the game. ‘[W]ithin living structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanisation, our feelings were not meant to survive,’ says Lorde. The Book That Defended Itself But you are a book. You are a Good Thing which must surely mean that other Good Things will come of you. Otherwise, why would we fetishize books to such a degree that we credit them with changing us, building us, making us the people we are? The Book That Made My Partner Block a Road was only part of a book — a short story called ‘The Falls’ by George Saunders. It’s written by a white middle-class cis man, and my partner is also a white cis man. This needs mentioning, in the context of books, and of access to the industry that sells them. Its two narrators – a young self-defined Writer who dreams of making waves, and an office-working middle-aged father – both spot two girls in a canoe, about to drown on a river. While the office-worker throws himself into the water, knowing that he and the girls will most likely drown, the writer is too busy debating with himself to do much at all. This story seems relevant to me, with regards to this list of books. There is nothing in it about being an activist, and there is no warning about what’s to come, what horror is enough of a horror to warrant action. What there is, I think, is ‘a quality of light’. Bacon Built This Body an old advert for bacon said. I used to see it on the tube in Stockholm. Really, I was built by nothing so easily packaged. I was built by my ancestors’ obsessions — colonisers and colonised. I was built by my brown skin in white Scandinavia, by the contrast between my two passports: one from ‘Viking land’ one from the ‘most dangerous country in the world’. I am built by how you want me and despise me, and yes, the books complicate things. They hold a space for complications. As such, at times they have saved me. These days, when I sit down to write, I think something along these lines: ‘this might just build me for what I do tomorrow’. Because writing is also that: not necessarily the change itself, but what fuels us in making change happen. The Books That Unmade Me continue to pick me apart, leaving me unready for what comes next — open only to how much I’m willing to leave the page. To try and unlearn dogmas, I also go back to those books. ‘(B)ut experience has taught us,’ Lorde writes, ‘that action in the now is also necessary’. Without it, books are all there is. Inside these ‘living structures defined by profit’, literature that presents only harrowing futures risks becoming an excuse not to tackle present violence. Books sold as activist may offer an excuse not to change the industry that made them, an excuse to stay within the pages of the book. The Books That Still Wanted to Exist But what else can we do, as writers? the audience cries. Write, and also, be more than a writer. Be the human you’d like to write about.

Jessica Gaitán Johannesson is a Swedish/Colombian writer and climate justice activist based in Edinburgh. Her debut novel How We Are Translated (2021) was longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize. She is Wasafiri Magazine’s Writer-in-Residence for 2021-22 and works as Digital Campaigns Manager for Lighthouse Books, Edinburgh’s radical bookshop. Her collection The Nerves and Their Endings: Essays on Crisis and Response is forthcoming with Scribe in August 2022. If you enjoyed this, read Jessica Gaitán Johannesson on control and climate disaster, her conversation with Daisy Hildyard, author of Emergency, or Irenosen Okojie's Global Dispatches piece 'Futures: African Imaginings' on climate change art and activism in Africa. Cover photo of Audre Lorde via Wikicommons under the Creative Commons Licence.