7 December 2020

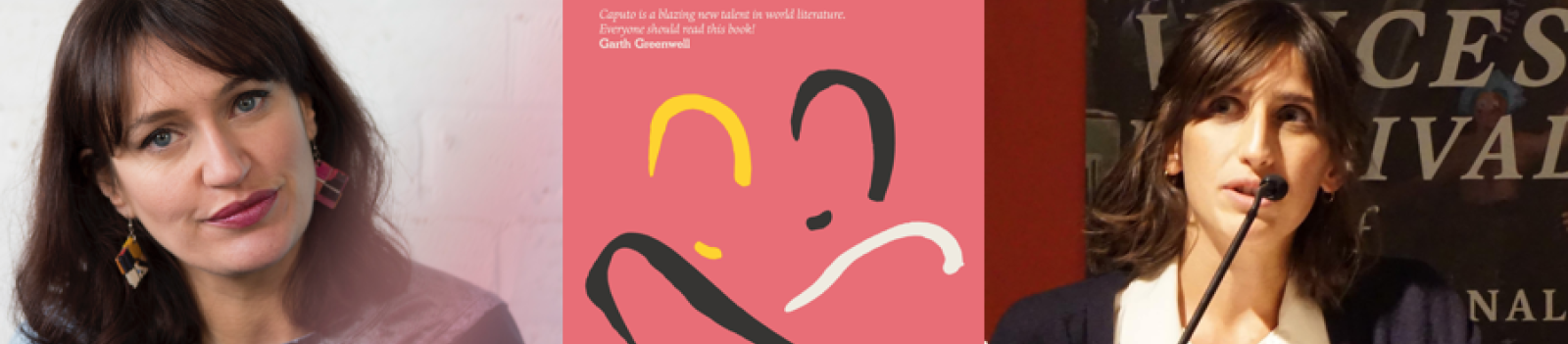

Wasafiri Wonders: Juana Adcock and Sophie Hughes

Ever wondered which book your favourite translator would secretly love to translate? Or a book in translation that may have slipped under your radar? Wasafiri Wonders is a series that asks these questions for you.

Juana Adcock is the author of Manca (2014) and Split (2019), which was a Poetry Book Society Choice. She has translated Gabriela Wiener, Diego Enrique Osorno, Giuseppe Caputo and Hubert Matiúwàa.

Sophie Hughes is the translator of authors such as Fernanda Melchor, Alia Trabucco Zerán, Giuseppe Caputo and Enrique Vila Matas. She is the co-editor of Europa28: Writing by Women on the Future of Europe.

1. Tell us about your translating rituals.

Juana Adcock: I like to translate on the couch with Candy the cat snuggled under my left arm. She prefers the left one for some reason. She helps me to stay put and concentrate.

Sophie Hughes: Snap. I often translate on the couch with candy, too, only it's sweeties on the sofa. I don’t have any real rituals.

2. Give us a metaphor for the author-translator relationship.

SH: In the worst-case scenario, an author delivers poorly edited or unedited work which the translator has to correct as they translate it to avoid looking like a shoddy, careless translator themselves. Something of a fisherman—fishwife situation, involving a fair bit of thankless, unsung and unpaid gutting and descaling.

JA: Gross, but very true. In the best case scenario, the author is a brilliant composer and the translator is an expressive pianist.

3. What is the best translating advice you’ve ever received?

JA: It was actually from you, Sophie. ‘Be bold’—which applies to all sorts of translation situations, from word choice to pitching to editors.

SH: And you gave me a piece of game-changing advice this week. When it comes to translating short stories or poems, don't automatically charge by the word. You're so right and I'd never thought about it. For reasons I haven't sat down to unpick, short stories and poems, more so than novels, beg to be left to sit after the first drafts, to be returned to and tweaked many times, and all that should be factored into the fee.

4. What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever had to translate?

SH: All the literature to do with dead, tortured, disappeared, abandoned people. The best piece I have read on this is by Lina Mounzer. She really gets to the heart of how language connects us to event in a sort of protected, controlled environment. But sometimes, as a translator, precisely because you have to pick apart the language, it cannot shield you. She writes: ‘Every time I think I have become hardened to these stories, a moment, an expression, a detail will throw me off the scaffolding of language, away from the structural safety of its grammar and rules and headlong into the wilderness beyond.’

JA: Documents about mining companies in South America. Finding out the intricacies of how big corporations extract resources and displace indigenous communities makes it harder to hope for a better world.

5. What’s a book you’ve read in multiple languages?

JA: The Little Prince. I've bought a copy of it in all the countries where I've spent any length of time. Because I pretty much know the text by heart, it allows me to fantasize about reading all sorts of languages that I will never even come close to learning.

SH: The Smartest Giant in Town by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. In Italian and English, and often. I tip my hat every time I come to the Italian translator Francesca Novajra's enormously satisfying rhyme, which isn't there in the original, 'il gigante più elegante'.

6. What's a book you think should be translated?

SH & JA: Giuseppe Caputo's new novel, Estrella madre!

SH: I can’t think of another one right now, but that’s probably because Spanish-language fiction gets the lion’s share of exposure where translation into English is concerned.

JA: I would also love to see any of María Luisa Puga's novels translated into English, but I have a particular soft spot for Antonia, which has stayed with me since I first read it, nearly 20 years ago. I feel like Puga, with her deceptively simple storytelling and her very broad international outlook, never quite got the recognition she deserved.

7. What’s your favourite untranslatable word in any language?

JA: At the moment it's the Italian 'confronto'. I actually wrote a whole poem about that word! It sounds a lot like 'confrontation,' which has quite negative connotations in English, but 'confronto', the way I understand it, seems to highlight the importance of spending time with and getting to know people through genuine conversation. Even (or perhaps especially) if they are quite different than you.

SH: That's beautiful. I love one from your neck of the woods, Juana. 'Ahorita' in Mexico means right away or right now, but how do you convey the underlying truth which is that it often translates in practice to some time this century or even... never! A bit like a British 'with all due respect'. The irony often implicit in a phrase like 'with all due respect' must be quite difficult to translate into languages that don't have anything like that phrase. Translating cultural habits or traits ingrained in language is generally tricky.

8. In your personal lexicon, how would you define/describe ‘translation’?

SH: Sedentary. Comforting. Liberating. Exposing. Constraining. Hard. Easy. Frustrating. Satisfying. Mine. Everyone’s.

JA: I love that. It really shows how intimate the process is. For me: playful, painfully detailed, and intriguing. A way to practice empathy.

9. What is your favourite book or pamphlet in translation published in the past year and why?

JA: Picnic in the Storm, by Yukiko Motoya, translated by Asa Yoneda. Because it was exactly the kind refreshing weirdness that I needed to survive the start of the lockdown, and the stories were the perfect length for bedtime reading. It was like a eucalyptus balm for my brain.

SH: It’s between The White Dress by Nathalie Léger, translated by Natasha Lehrer and Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah, translated by Deborah Smith. There are also books I probably won’t remember but whose translations were inspiring. That happens to me a lot. I marvel at the balance of precision and charisma achieved by some translators.

10. If your newest work in translation were a music album, what would it be and how would it sound?

SH: It’s Fernanda Melchor’s new novel, Páradais. She grips us from the get-go, but the action absolutely explodes in the final quarter. It would sound like Radiohead's 2 + 2 = 5, the quiet before the storm that breaks with: You have not been … payin' attention!

JA: I'm now going to have that going round and round in my head until the book is published! I love that song. Mine is a poetry collection by Hubert Matiúwàa, and it would sound like the 1975 album Maya by Bolivian psychedelic rock band Wara. Sounds that span whole mountains and valleys, and the voice of the wind whispering at times and at others crying out. Both epic and intimate, stopping and starting, suspense, thunder.

An Orphan World by Giuseppe Caputo – translated by Juana Adcock and Sophie Hughes, and published by Charco Press – was reviewed in Wasafiri 104, ‘Human Rights Cultures’, which you can buy in our online shop.